The Double Refuge 🇲🇽 Señor Locke

In the Valley of Darién

2000 - Alfred J. - Timelines: The Fall of the Epic

☕️

2000

The waitress is still sitting across from me. She’s looking up at the clear blue sky, yet I don’t know if what she thinks about is just Guanajuato in the year 2000, or also Golgotha 2000 years ago. I’m unable to juxtapose the two. But is she?

I’d love to write about this woman, fit her somehow into a story about Modern-day Mexico, yet there are at least two things that give me pause. First, I don’t know how she feels on the most basic level. How does she touch the world and how does the world touch her? I may have my own sense impressions, but these go from my fingers to my brain, and from my eyes to my brain. By every spatial fact known to phenomenology, I can’t pretend to know how her sense impressions go to her brain. Second, I don’t know how she turns these sense impressions over in her mind, to create a second, more complex realm of meaning. Does she feel the cross and think of Jesus?

☕️

Alfred J.

I’m reminded of the predicament T.S. Eliot explored in his 1915 poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Eliot’s anti-hero sees a group of women talking about art, and is afraid to approach them. He’s distracted by the “Arms that are braceleted and white and bare,” and he feels that they’re judging him before he even has a chance to open his mouth. He fears “The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,” and he feels “formulated, sprawling on a pin, … pinned and wriggling on the wall.” It’s as if the women can see right through him, like the recently-developed X-rays machines: “as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen.”

Even if Prufrock had the most profound experience, even if like Lazarus or Dante he travelled to the Underworld and back, he worries that these woman wouldn’t care:

And would it have been worth it, after all,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it toward some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all

If one, settling a pillow by her head,

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all.

That is not it, at all.”

What Eliot gets at so comically and tragically, and in such a loose yet coherent way, is the inability to connect in our understanding of what’s important. We’re separated by gender and by all kinds of things — personal interest, education, language, race, culture, etc. Moreover, there are no overarching Truths with a capital T that can knit together all of our diverse understandings into a greater or overwhelming unity or plan. E.M. Forster counselled, “Only Connect,” yet the basic empirical fact becomes the basic phenomenological fact: humans don’t have neurons that they share. Fundamentally, we do’t connect. While we can share the same input of music or colour, we’ll inevitably process these inputs in different ways. And the differences only multiply the more we go from basic understandings of things like sound and colour to complex things like meaning, interpretation, ideology, and belief.

Prufrock wants to follow in the epic wake of Dante, who takes us on a journey through Hell and up to Heaven, yet Eliot lies on the other side of the Renaissance from Dante. He lives in a world where the Bible is no longer the grand narrative, and in which the combined facts of astronomy, geology, and evolution have thrown into doubt everything religion has to say about life, death, and the meaning of human existence.

At the end of Eliot’s poem, Prufrock admits total defeat. He may see the mermaids “Combing the white hair of the waves blown back / When the wind blows the water white and black,” yet unlike Odysseus he won’t have an encounter with the mermaids. He says he has “seen the mermaids singing each to each,” but bluntly adds, “I do not think that they will sing to me.” Even this denied fantasy, with its image of the mermaids with their hair blowing in the salty wind, is drowned out by the salon women who don’t care about what he’s saying. The poem ends with the line, “Till human voices wake us, and we drown.”

☕️

Timelines: The Fall of the Epic

In the 17th Century poets could still believe in the miracle of the cross that transcends time itself. They could believe that their existence on this earth wasn’t the main fact, but was superseded by their eternal existence, which was to occur in a place called Heaven. In his sonnet “Death Be Not Proud” (1609, 1633), John Donne writes “One short sleep past, we wake eternally / And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.” In the opening lines of Paradise Lost (1667, 1674) Milton says that we live in a world of death and woe, yet Jesus will transport us into a realm of eternal bliss:

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit / Of that forbidden fruit, whose mortal taste / Brought death into the world, and all our woe, / With loss of Eden, till one greater man / Restore us, and regain the blissful seat, / Sing heavenly muse […]

Because Milton accepted the Grand Plan offered by Christianity, he could write earnestly about the temptation in the Garden of Eden. He could write confidently about the cosmic battle between one legion of angels and the next, and about the epic journey of Satan through the realm of Chaos to the Gardens in the Sky. Like Dante in his Divine Comedy (c. 1321), Milton could infuse these malleable mythic realms with a rock-solid theological meaning that surrounds the drama and gives comfort to frail humanity — just as Dante’s Virgil (who guides Dante in the Divine Comedy) is comforted during his harrowing journey through Hell: his journey, like Hell itself, is controlled by the will of God.

Although deeply Christian, Dante’s Divine Comedy is deeply indebted to the Greek and Roman epics of Homer (Iliad & Odyssey) and Virgil (Aeneid). His mix of Classical epic and Christian theology is picked up by Milton, who writes just before the Enlightenment (also called the Age of Reason and the Neoclassical Age), which goes roughly from the late 17th Century to the late 18th Century, at which point the Romantic Age begins.

During the Age of Reason English poets never managed to write a great serious epic in the tradition of Dante and Milton. Perhaps they were too aware of the pedestrian nature of their contemporaries. Given the biting nature of much of their writing, one might even say, their contemptoraries. Although a person might puff themselves up into the guise of an epic figure, the poets inevitably revealed the grandeur to be a sham. Hence the mock epic, which takes many of the epic conditions and deflates them — as we see in Dryden’s Mac Flecknoe (1678, 1682) and Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712-17) and The Dunciad (first version 1728, 1743). Later, Byron in Don Juan (1819-24) and Joyce in Ulysses (1922) deal further blows to the sublimity that once characterized the epic.

Among the second generation of English Romantic poets (principally Byron, Shelley, & Keats) the pull of Classicism was very strong. Yet instead of fusing the Classical epic with Christianity, they fused it with a wide variety of possibilities, from the aesthetic agnosticism of Keats and the satiric agnosticism of Byron to the abstract neoplatonism of Shelley.

We can see the high regard of the Romantic poets for for the author of The Iliad & The Odyssey in the first two quatrains of Keats’ 1816 sonnet,"On First Looking into Chapman's Homer":

Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow'd Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold

In terms of timelines, Keats lies at the other side of the Enlightenment from Milton. It’s not surprising therefore that he tried to write a cosmic epic, this time pitting one generation of Greek gods against the old. Nor is it surprising that he couldn’t get himself to really believe in the project. He said that it all seemed too Miltonic. Too grand.

In Keats’ day — between the geology of Hutton (1788) and the natural selection of Darwin (1859) — the Grand Plans were crumbling. It became increasingly difficult to believe in the biblical timeline and in the combination of epic format and religious meaning that was used by Dante and Milton. Increasingly, it didn’t matter if one wrote the Christian epic high above the Aonian Mount or on the peak of Sinai. Both mountains were fast becoming physical mountains, stripped of their metaphysical, essentialist magic.

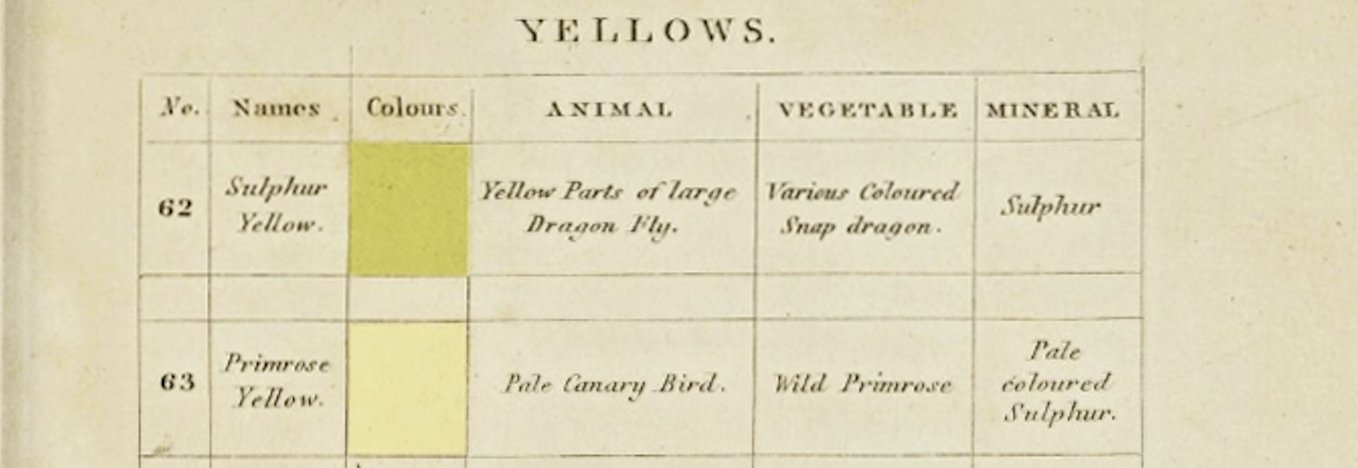

We see this shift in the perception of sacred mountains in the geological timeline published by Abraham Werner at the end of the 18th century. Werner’s timeline isn’t concerned with angels or images of the Flood. Instead, Werner uses a colour-scheme for minerals — a scheme that was later used by Darwin.

Helicon and Olympus were once surrounded with a quasi-religious awe, and Sinai was once surrounded with an overtly religious awe. But from the geological perspective of the late 18th century they are seen as layers of rock that have shifted over a massive time-frame. As such, they are the same as Athos, Oreb, Sinai, Kailasa, Tai, Emei, Fuji, Agung, Croagh Patrick, Shasta, and all the others that once seemed to reach beyond the earth and into the heavens. This basic fact was becoming more and more clear, especially by 1788, when James Hutton published his Theory of the Earth; An Investigation of the Laws Observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globe.

What could such mountains mean once metaphysics gave way to geophysics, and once Locke’s sense-driven brain computed the numbers that continued to come in thick and fast from the Natural Sciences? More definitive numbers came in with Darwin in 1859, dealing a final blow to the old time-line that started around 4004 B.C. The old time-line that started with Adam and Eve in a place called Eden.

Keats nevertheless tried to make something grand of it all, linking the rise and fall of the gods to his present day: The Fall of Hyperion: A Dream and then Hyperion: A Fragment — two uncompleted epics about sunken gardens, skies riven, old orders overturned by the new. All these we see in his image of his Titan king, stalking the courtyard of a ruined empire:

Deep in the shady sadness of a vale / Far sunken from the healthy breath of morn, / Far from the fiery noon, and eve’s one star, / Sat grey-haired Saturn…

Thus begins Hyperion; A Fragment, written before his TB and the coughing up of blood, 1819.

☕️

I could try to follow in that Miltonic mode, writing a Mexican epic from somewhere near the peak of Popocatépetl. I could turn Cortés into Odysseus and put him on high, as in the final lines of Keats’ sonnet about reading Homer:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Yet where would that leave the real world — the world of the senses, of jade ear-rings and silver necklaces, of geography and history, of real time and space? Where would that leave the here and now, the simple here and now, beneath the umbrellas of Van Gogh’s Ear?