The Double Refuge ❇️ Aims & Terms

The Unconvinced

The Courage of Your Non-conviction - The Convinced - The Over-convinced - The Unconvinced

❇️

The Courage of Your Non-conviction

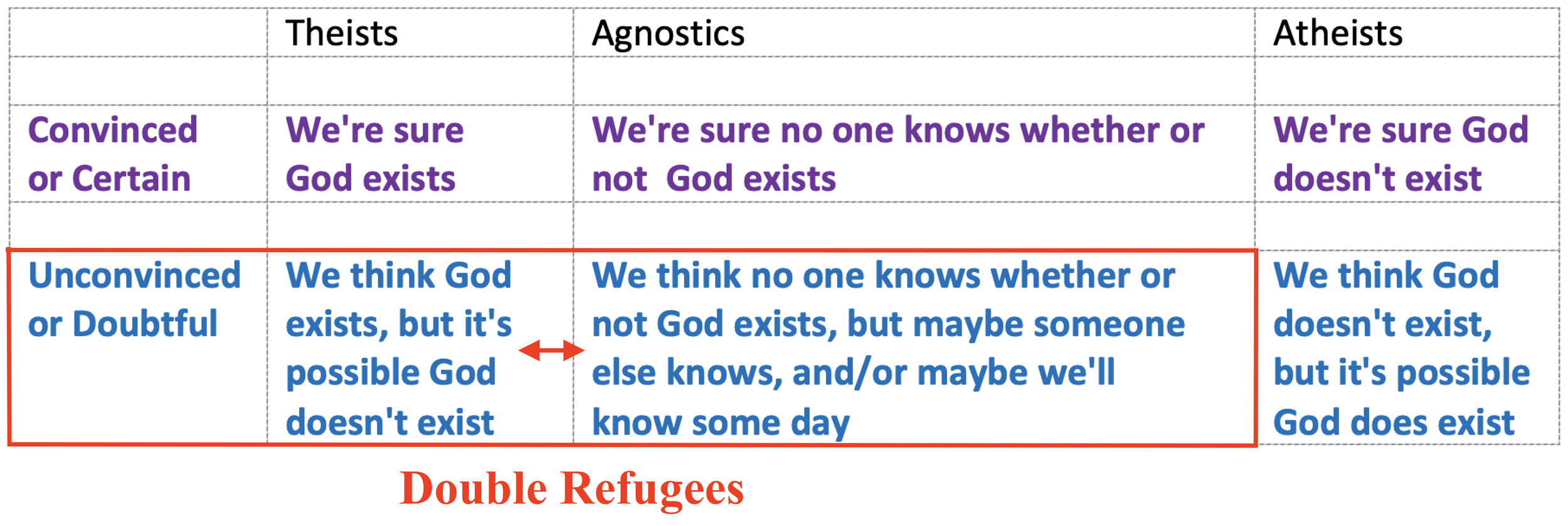

While theists, agnostics, & atheists inhabit the distinct categories of belief, doubt, & disbelief, a large percentage of them are more alike than they seem. We can see this when we bisect the three categories into two further categories: the convinced (or certain) and the unconvinced (or doubtful).

Double refugees operate within the theists and agnostics categories in blue below:

Double refugees may believe or suspend their belief, yet in either case they don’t profess to have the final truth. They doubt too much to join the believers, and they believe too much to join the doubters. At times they believe more and and times they doubt more. Their position is a composite of two positions, and they don’t rule out that they may at some later time become more convinced or certain.

Scholars like Bart Ehrman, Richard Rohr, and Peter Enns are helpful to double refugees in that they look at religion in very flexible and open ways. They see the Bible as a multifarious attempt to understand God. They see it as a collection of books which aim at divine truth, but are always imperfect — except insofar as they lead us to deeper or more significant meanings. For instance, Ehrman sees the two versions of Creation in Genesis as two propositions, two guesses in the dark. An even more daring series of guesses can be found in Rg Veda. In this text (from around 1450 BC) there are numerous versions of Creation, all ultimately pointing to the notion that we really don’t know how we got to be where we are. In the most famous of these guesses, the poet writes that even the God in the highest Heaven may not know.

Double refugees take this to heart. While their positions might be seen as waffling and fence-sitting, from another angle their view is the most solid, in that it seems quite probable that no one really knows the answer to these questions.

❇️

The Convinced

The convinced group have the courage of their convictions. They believe that their truths are universal and that they could or should be accepted by everyone. If others have a different understanding, they are not properly informed, sadly mistaken, misguided, or willfully wrong.

🔺 For convinced theists (often called traditionalists or fundamentalists), truth reverberates from the Wisdom of the Ages and from hallowed books like the Bible or Qu’ran.

🔺 For convinced agnostics (also called hard, permanent, closed or restrictive), truth comes from the conclusion that neither religion nor science has the ability or the authority to make pronouncements about the ultimate nature of reality.

🔺 For convinced atheists (the more extreme among them being positivists or New Atheists) truth comes from the ever-widening knowledge of science, which establishes a solid base of understanding and meaning.

From the point of view of the double refugee, these are all perfectly valid positions to take. Refugees do, however, observe a degree of internal contradiction in the positions of convinced scientific atheists and convinced existential theists.

While the dangers of fundamentalism, zealotry, and puritanism are well known (Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” and Scarlet Letter are instructive in this regard!), we often overlook the irrationality of those who hold up rationality as the only truth: positivists and New Atheists. These two overlapping groups of atheists tend to wield science as a weapon. They also assume that science can only shoot in the direction they aim.

Fundamentalists, positivists and New Atheists may be right in the end, that is, once the clouds of Heaven part, or once the subatomic and astronomical fields are unified into one grand theory. Yet until such time, moderate thinkers are right to question the value of going out of our way to exclude all other options.

🦋

Positivists & New Atheists

When it comes to Positivists and New Atheists, double refugees would remind them that while science can prove things, it also demonstrates how little we know.

It may at first seem odd to claim a divide between convinced atheists and scientists. Yet the convinced atheist believes science has proven there’s no God. Or, they reason that the lack of proof about God proves that there’s no God. The scientist on the other hand believes science may one day prove there’s no God, but it hasn’t proven it yet. I’d go so far as to say that convinced atheists can’t really claim to be scientists, at least not in the philosophic sense, for they reach conclusions that science hasn’t reached yet, or may never reach. In brief, they mistake hypothesis for verification.

Oddly, it’s more consistent for theists of a mystical bent to be scientists. In affirming their belief in theism, they’re affirming a belief, not a fact. They affirm something which has nothing to do with logic or science, something they don’t pretend to prove. I should add a crucial caveat here: my argument only works with open, syncretist, or mystical theism, not with any fundamentalist theology that makes specific claims about time and space — that is, claims that might be disproven using archaeology, philology, or history, or contradicted by other religions which make similar claims.

By mysticism I mean the following — from the Apple dictionary:

1. Belief that union with or absorption into the Deity or the absolute, or the spiritual apprehension of knowledge inaccessible to the intellect, may be attained through contemplation and self-surrender: St. Theresa's writings were part of the tradition of Christian mysticism. 2. Vague or ill-defined religious or spiritual belief, especially as associated with a belief in occult forces or supernatural agencies.

I agree with this definition in the general direction it takes, yet not in its use of the negative terms vague and ill-defined. From a double refugee’s point of view there’s no clear definition of God or spiritual essence, so it’s odd to use the word vague. Amorphous, varied, syncretic, etc. would be more accurate, and less subtly pejorative. It’s also odd to use the word ill-defined, because lack of definition isn’t ill in itself. Likewise, in describing outer space, ill-defined is less helpful than infinite, beyond our scope, subject to our changing knowledge, etc.

I’d argue that elusiveness even works to the open theist’s advantage in regard to science. The more language escapes the demands of verification and proof, the more likely it is to be of interest to the open-minded scientist — and of disinterest to the positivist who requires scientific proof for something to be true. For instance, imagine that someone says there’s a three-headed angel-fish in the Amazon River. The convinced atheist might insist there are no three-headed fishes and certainly no angels. The scientist on the other hand might say that Nature often has surprises in store, so let’s look into this claim.

The same pattern emerges if a mystic says that the universe is throbbing with an energy that lies beyond all meters: the convinced atheist might insist that nothing lies beyond all meters, while the scientist might be doubly intrigued — at first by the claim of the energy itself and secondly by the thought of making a meter sensitive enough to measure what some say can’t be measured. They might be curious to hear mystics talk about an airy nothingness which yet has an essence. They might wonder what mystics and poets mean when they use words such as ether or akasha to describe an aspect that seems to be air or emptiness yet has a dimension, emanation, essence, ghost, etc.

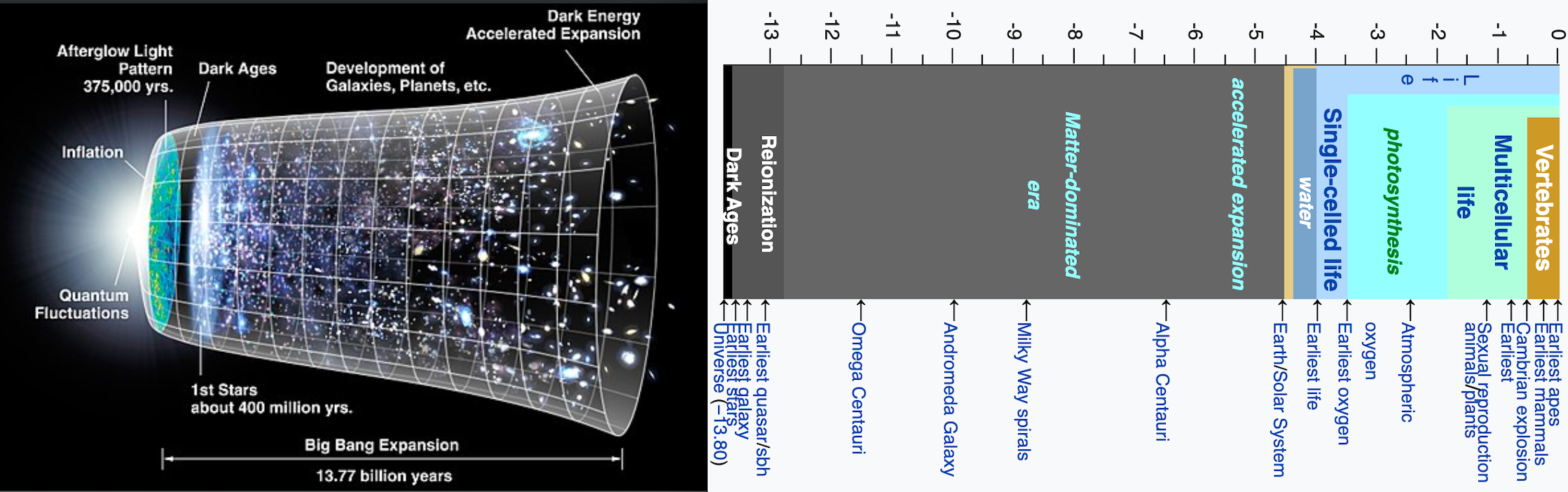

Many non-theists come too quickly to the positivist conclusion that if they can’t verify something it therefore isn’t true. They assume that many of the great scientists believed in God because they had a blind spot or because their belief was a relic of their backward Age. Yet there never was, and still isn’t, a conflict between science and abstract theology and mysticism. Indeed, one might say that the rational scientist and the mystic meet at the point of infinity and in the subsequent annihilation of the finite self. We are tiny dots in an immensity, whether it’s the notion of God or exoparsecs that gets us to that understanding.

It may be that the infinity imagined by scientists and mystics constitutes a gospel of sorts. This gospel is a powerful one, especially if it combines open-mindedness with love and compassion. Doctors without mental or emotional borders may believe in God or they may believe in the laws of Nature. Yet the most important, perhaps even transcendental reality, is that they believe in helping others.

❇️

Theistic Existentialism

Positivists and New Atheists limit the options open to exploration, throwing five thousand years of doubt and belief to the wind. Religious fundamentalists do much the same when they fence off a multiplicity of religions and philosophies, labelling them pagan, idolatrous, sacrilegious, and vain.

In looking at theology, it’s crucial to distinguish between 1. theology based on abstract and mystical claims, and 2. theology based on specific claims about astronomy, physics, miracles, history, society, politics, etc. While abstract and mystical claims can’t be proven wrong, specific claims can be proven wrong or derivative.

For instance, it’s impossible to prove or disprove the existence of the Holy Ghost, the Good, Brahman, Akasha, or the Dao. None of these purport to be located in our conventional four-dimensional space-time grid. On the other hand, 🔺 water can’t turn into wine without grapes and a wine-press, 🔺 the world doesn’t stand still in space, as the early Greeks and Christians believed, and 🔺 the Hebrews didn’t come up with the notions of an angry god, a flood, an ark, and a new covenant. The Mesopotamians came up with these notions.

This doesn’t make the Hebrew notions wrong; it just means they’re not original. The monotheism of the Hebrew account may be original (barring influence from Egypt or Iran), yet the epic narrative and the notion of divine interference, deliverance, and covenant is not original. The story of a great flood may one day be verified by science, but what the Hebrews value so greatly — the notion of a covenant with a monotheistic God — remains as resistant to verification as the notion of a pantheon of gods.

From a more moderate religious position, it makes sense to let go of the historical and literal claims in favour of a more abstract focus on spiritual essence, divine love, an invisible force of redemption, service to others, love, hope, faith, charity, etc.

From the 15th to the 20th century, theological systems that insisted on pre-scientific knowledge, a specific historical timeline, and supernatural acts became more and more difficult to believe. Astronomy, geology, evolutionary theory, Mesopotamian philology (Assyriology), genetics, and neurology came together to provide a fact-based explanation about 🔺 how the natural world works, 🔺 how we came to be who we are, and 🔺 how the human mind works. Some felt that it became necessary for believers of a rational or scientific bent to take a leap of faith, passing over the incongruities and contradictions of specific religious claims to land on the side of belief. Some even used the term Christian existentialism to describe people who believe in the explanations of science yet also in the mysteries and miracles of Christianity.

From a double refugee point of view, there are two problems with this version of existentialism. The first problem revolves around the words used: once one has made a leap from existentialism to Christianity, one leaves the notion of existential behind, yet the term Christian existentialism retains the existentialism. The second problem is that making a jump may be wonderful for the leaper, yet it doesn’t mean we have to accept the hierarchy of saved over lost, spiritual over physical, moral over amoral, etc. It’s one thing to have both these elements in our psyche, and allow both to operate as in the double refuge, yet it’s another thing to assert that the spiritual is then superior to the existential. It seems more accurate to call such a person a Christian who was once an existentialist.

Not that one can’t make this jump, and not that this jump isn’t a good thing to do. That’s up to the jumper! It’s just that the result can’t bridge the gap between the categories of existentialism and essentialism once one has decided that the essentialism is the true and proper category. According to the double refugee, the jump doesn’t confer superiority of one over the other.

The term Christian existentialist (or Hindu existentialist or any type of theistic existentialist) combines two fundamentally different meanings: an existentialist life means living without the essence of soul or God in this material world, whereas an essentialist life means living with an essence of soul or God. This is the fundamental distinction made by Sartre, and it is a distinction built into the term existential itself — to exist, that is, to exist alone or by oneself, without aid, intervention, or punishment from some otherworldly essence, whether this be a god, God, Force, Absolute, demon, or angel.

Sartre codified this term in the Modern context, yet even in the Middle Ages people understood that there could be 1. a material or physical world, and 2. an immaterial or spiritual world. They understood the difference between 1. those who believed only in the material world (then called unbelievers or materialists, later also called existentialists) and 2. those who believed that there was an essential or spiritual world shadowing or dominating the physical one (then called believers, later also called essentialists).

Any wording such as theistic existentialism suggests that the adjective refines or further defines the noun, which is the principle subject. Christian existentialist doesn’t really work as a defining term since the main belief is Christianity, not existentialism. Here, the Christian escapes or leaps from the uncertainty, alienation and chaos of existentialism. This leap initially resembles that of the double refugee, who pivots from existentialism to open theism. Yet in the case of the refugee, it’s a temporary refuge, and the refugee doesn’t stay in the theistic long enough for it to become the dominant category. The double refugee doesn’t escape the existential for the essential; rather, he takes refuge, until the refuge becomes less habitable and he pivots back to the world of existentialism, which becomes a refuge from doctrine, dogma, puritanism, exclusivity, etc. — but not for long, because he may soon be lured by some ineffable form of beauty in the essential realm. This time he isn’t seeking refuge so much as mounting a stair up to some brighter, more airy viewpoint. It doesn’t mean he thinks that the ground floor in any way inferior. Indeed, without a ground floor the upper floors would become inaccessible, collapse, or float off into space.

While there’s a great deal of phenomenological overlap between agnosticism and existentialism, agnostics don’t claim to be existentialists. Both are philosophies, and for an agnostic to claim to be an existentialist would be like a stoic claiming to be a skeptic. The boundaries are fine, even translucent, even invisible, but they’re there nonetheless.

The problem of boundaries is even greater when it comes to Christian existentialists, since they’re not just overlapping philosophies, but distinct categories: belief and disbelief. One might say, sometimes I feel like a stoic and sometimes a skeptic, and likewise I believe at certain moments and disbelieve at others. Yet it’s far more problematic to say that you believe and disbelieve at the same time. Perhaps one way to say I’m a Christian existentialist would be to say I alternate between Christianity and existentialism. Or I inhabit the contradiction of my position, believing and not believing simultaneously. Yet this stance seems rather close to schizophrenia or madness, for it isn’t asserting I live in an existential material world yet believe in another world, but rather it asserts I live in two very separate worlds at once. In one world miracles aren’t possible. In the other world, they are.

The open refugee gets around this problem by not accepting that one is better than the other. Essentialism isn’t better than existentialism, and essentialism isn’t better than existentialism. The nature of both are so debatable, and are in fact so ill-understood, that one can go from one to the other without worrying about it.

The border guards aren’t just on a break. They’re so drunk that they’re happy to see anyone go in either direction without so much as a blurry glance at a passport.

❇️

The Unconvinced

Returning to my chart, I would suggest that there are fewer contradictions in the positions of the unconvinced.

The unconvinced think that belief, doubt, and disbelief are subject to interpretation and re-interpretation, to the historical moment, to one’s philosophical predisposition, to cultural bias, linguistic orientation, etc. The unconvinced suspect they’re right, but they’re not convinced they’re right. As a result, they avoid certainty, whereas the convinced embrace it. In terms of problematic positions — such as those of convinced scientific atheists and existential theists — the unconvinced are less vulnerable: because they doubt their views, any solid idea or any contradictory idea they have will be subject to their own doubts. They can look discrepancies and contradictions straight in the eye, without a pre-established agenda to confirm them or to deny them.

The unconvinced group is in line with a generalized search for truth, which makes those with an interest in theology lean toward mysticism rather than organized or historical religion. It also makes them lean more toward epistemology (the study of how we arrive at any truth) than to established schools of philosophy (which tend to explain ways that truth can be established). One might even argue that unconvinced theists, atheists, and agnostics are more aligned with each other than they are with people who share their beliefs yet insist on them. This is perhaps an uncomfortable point for convinced agnostics, given that they stand rather uncomfortably on the same ground of certainty as those who have stepped through the door of belief and those who have slammed it shut. To continue the metaphor, convinced agnostics jam the door open and stand on the doorstep. Unconvinced agnostics see the open door, but understand why some might want to close the door once in a while. Moreover, they like it when the door is open because that allows them to slip from one side to the next.

Convinced theists, in arguing with unconvinced theists, might argue something like the following: Although you can’t prove God, you can nevertheless feel Him. Although you can’t grasp Him by logic and reason, you can nevertheless believe in Him. Why wouldn’t you actively believe in what is by definition operating on the levels of feeling and belief? The convinced theists have a strong case here, and this partially explains why so few theists tend to doubt their belief. One must of course include the psychological and social benefits of a clear belief in an all-penetrating sense of Meaning and in the notion that the ultimate Power in the universe cares about us. In addition, there is escape from sin and punishment, clear moral laws, universal justice, the promise of an afterlife, etc. With all of this on offer, why go so far as to believe it if you don’t commit yourself to this belief?

Agnostics on the convinced side might object that there's no philosophical position, or there’s little value to a position without a firm belief in that position, yet the agnostic thinks the value lies in 1. a realistic view of the universality of doubt, and 2. a stand which allows you to explore all sides, deeply and objectively, that is, without wanting to prove them right or wrong.

Convinced agnostics might also argue that unconvinced agnostics have dogmatically committed themselves to eternal indecision. While convinced agnostics may be firm in their assertion that no one can claim to know an ultimate truth, from a subjective or phenomenological point of view it seems valid to concede that while agnostics don't know an ultimate truth, others might. The convinced agnostic appears to have a point when they argue that the deep skepticism of the unconvinced agnostic is a version of a universal truth, since unconvinced agnostics don’t waver in their conviction that they may be wrong. Yet there are two problems with this logic.

First, it’s difficult to refute someone who says that they might be right or they might be wrong. Even if convinced agnostics proved that conviction is right, this doesn’t contradict the position of unconvinced agnostics, since they already admitted they may be wrong. Their response would be, Yea, we imagined that was the case, anyway. Such a certitude wouldn’t necessarily make them happy, nor make them sad, since what they lose in hope for an essence is countered only by the proof that we’ll never know if they have an essence.

Second, the convinced agnostic’s argument may be a contradiction in terms, for it mistakes the observation of change for the constant of change. Unconvinced agnostics would object, How can you say that everything changes yet then say that change stays the same? The observation of continual change doesn't mean that unconvinced agnostics believe change to be a constant — and this for two reasons. First; saying that change is a constant doesn’t mean that constant is equal to unchanging; rather, in this context it means occurring in every observation, which verifies that change occurs. Second, unconvinced agnostics remain open to the possibility that some things don’t change. Unconvinced agnostics are comfortable with the notion that tomorrow they may believe something else. Like scientists, they take their present knowledge to be contingent, provisional, and conditional. It all depends on the ontological situation of the moment and on the present historical and personal state of their human understanding.

❇️

Next: 🍏 On Liberty