Le Bijou 3

The Third Act

Madame Dupont

Madame Dupont came an hour early to the lecture hall in the Collège de France. She wanted to be inside the building again. To breathe it in. For this is where her life had taken its happiest turn.

An emeritus professor of Philosophy at the Sorbonne, she’d recently bought an apartment several blocks away, out of nostalgia for the old days in the Latin Quarter. It was there, in the Fifties, Sixties, and Seventies that she had become who she was: a free-thinker of the post-war era. Then, one afternoon back in 1979 she attended a lecture on Epistemology at the Collège. By chance, she sat down next to a visiting scholar from England. Here, in this very room. This very seat.

They were married within a month, and their marriage lasted 40 years. Throughout that time they lived Chagall’s lovers in an ocean of red love. My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag.

Conrad died two years ago, in a different room, one with tubes and visiting hours. He now lay in the Montparnasse Cemetery, with all the other souls she’d known along the years. From the tower above, it reminded her of the fields of death she had seen as a girl in Poland.

She was adrift in this, her final act. She couldn’t stand to walk along Montparnasse Boulevard without Conrad, so she got a place in the Latin Quarter and spent her days walking the old blocks, from the Pantheon down to the river, in search of her old self. The one she left behind when she met Conrad: the proud bohemian queen who had no intention of dying of TB or any other disease which might make her feel faint.

Madame Dupont was looking forward to the speech by the visiting professor from Oxford. It made her think back to her year there, where she read Lewis Carroll while Conrad looked after his dying father. She wrote several articles comparing Carroll to her philosophical mentor, Blaise Pascal. She still believed in what she wrote, about how both men escaped a meaningless world by using ruthless logic, and then by overwhelming this logic with an even more ruthless use of metaphor.

Her mentor and nemesis, Blaise Pascal. She loved his mathematical mind, but couldn’t accept how everything ended with God. God and the Catholic Church answered all the questions that couldn't be answered. It perplexed her that Pascal started off with numbers and ended up with God. And it depressed her even more that no matter how she worked the equation, all she could end up with were numbers. Perhaps Pascal’s philosophy worked back in 1660, when there was no equation yet for the energy that could be derived from a mass of uranium.

Above all, Pascal's God didn't make sense to a Jewish girl who had managed to rise from the ashes of of Auschwitz. A French Jewish girl with curly black hair and incandescent eyes.

Her eyes were watery now (there were tiny rings around her light brown irises), yet Pascal still made her blood pressure climb. How could he be so rational, and yet so irrational at the same time? She thought that when she got older, she'd learn to accept this, as if proximity to death would make some paradoxical logic appear somehow. It never did.

It would’ve been a relief to believe that she'd see Conrad again, in some otherworldly Paris, deep in the clouds. A City of God with croissants and seven-story buildings like the one they lived in on Boulevard Montparnasse. But even at the age of 76 she couldn't see it.

As she walked along the Seine, the lovers on the quay filled her with indescribable pain.

The winding river, the luminescent limestone buildings hacked from the nearby quarries of the Oise, the cafés jammed with poets and artists, these were the things that remained constant for her. The patrons may change, the Samaritaine might get a makeover, but the city of men remained.

Yet the men in the city came and went. And one man never came back.

These were the hard truths upon which she constructed the scaffolding of the world. She stepped into Notre Dame, but she stepped out again. Once back on the pavement, the gargoyles blocked the angels above.

She had tried to face all things as they were, unvarnished with what she might want them to be. At 76, she was still sane enough to see that anything else could only be categorized as la belle espérance. And now, after her careful, creative, ruthless construction, she lamented that she couldn't climb to the skies.

☆

As a philosopher, Madame Dupont had always been preoccupied by definitions. And this is where she parted with Pascal, who argued (in De l’esprit géométrique et de l’art de persuader) that since reality could only be quantified (geometrically and mathematically) by using axioms, then reality must find its ultimate axiom, its ultimate definition, in God. Despite what seemed to her Pascal’s existential leanings, he insisted that the meaning of axioms (those things we feel to be true, but can’t prove why they’re true) must reside in the mysteries of God. Everything that’s relative, so beautiful in mathematics and geometry and yet so untrustworthy in human thinking, must find its deeper coordinates in The Eternal.

Conrad and she used to laugh whenever they heard this kind of reasoning. Sitting opposite each other in their shared study overlooking the boulevard, they’d cry out in unison, Siècle des Lumieres! in much the same way the French used to exclaim Sacré bleu! or the Québécois still cry out Tabarnac!

Now, beneath the majesty of the Gothic arches, her laughter stabbed at her memory and she felt differently. Quite frankly, she wished that she’d chosen to believe.

And yet still she couldn’t do that. Pascal’s thinking reminded her of the Medieval take on Aristotle: if you can’t find ultimate causes in this world, find them in another world. In Creation, the First Cause, Alpha. Then loop this Alpha to the End of Time, the Final Effect, Omega, and abbracaddabbra, you close the Circle of Meaning.

In her fourth book, Point De Départ, Madame Dupont started off with the simple observation that there were more than two letters in the Greek alphabet. The scientific uses of these letters couldn’t have been imagined by the Greek writers of the gospels.

Instead of pointing to a Prime Mover of numbers that transcended numbers themselves, the study of Mesopotamia pointed to the practical origin of numbers: trade, vats of wine, and bushels of barley. These they counted in base ten and base sixty: 10 X 60 + 6 X 10 + 6. In the eyes of the Chosen People, and the people who then chose themselves, the numbers of business became strumpet numbers. The Whore of Babylon! 666! Passing through the mystery cults of the Classical world, these demonic digits danced into the bonfires of the Medieval mind.

But of course Pascal couldn’t have known back in the 1650s about the secrets hidden in the cuneiform script of the Mesopotamians. These secrets remained buried until the mid-19th century. And despite Pascal’s claims about revelations, axioms, and intuition, he couldn’t have intuited it either. He couldn’t have known that letters (even the Word, sacred as it may be) and numbers (from the demons of 666 to Plato’s ladder of mathematical Truth) were simply historical constructions. Endless sequences of markings in clay. Digits on screens. Circling around us, with no diameter and no intrinsic pattern.

These were the hard facts that as a French woman she’d known since university. The years with Conrad, from the barricades to their apartment in the fifteenth arrondissement, didn’t change them. The facts were fixed, solid, almost as comfortable as their lives together in their second-floor apartment above the cafés of Boulevard Montparnasse.

Until, that is, he died. Until she came back to the Latin Quarter to try to remember who she once was.

☆

On the Podium

At precisely 2 p.m. Kenneth began to speak. The lecture hall was three quarters full, which was impressive given that a famous scholar was also giving a presentation on the Louvre exhibition, Artifacts from Uruk. Kenneth looked into the crowd to see if Martine was there.

Scanning the audience he could make out a sea of olive green cardigans and light blue chiffon dresses. A froth of grey-white hair floated above them, like lines of cirrus clouds in an evening sky. Kenneth felt faint, and wondered if Martine had doubled back to La Maison de Verlaine. Or perhaps she’d arranged to meet him at Le Bateau Ivre. They were probably on their second bottle already, like drunken sailors. Why didn’t he talk to her at lunch? Why didn’t he just tell her he was in love with her?

He saw that she had decided not to attend the lecture.

As soon as Kenneth started to speak, he saw the light on his cellphone blinking on the lectern. Below it: “MARTINE.” Why on earth would she call me now? She knows I’m just starting my lecture. It must be an emergency.

Kenneth begged the forgiveness of his audience, and answered the phone. “What is it?”

“Antoine got the contract!”

“You called to tell me that? Don’t you remember that I’m in the middle of — ”

“Bon Dieu! Half the audience is senile. The other half probably doesn’t know what a cellphone is.”

“Martine!”

“He's invited me to Japan. Should I go?”

☆

Madame Dupont was sitting in the front row and could see everything Kenneth was doing. She was on the far end of the row, and could almost see what was on his little screen, as he danced back and forth on the podium. She was sitting right next to the exit, and he kept looking at the door. When he looked over (nervously, like the White Rabbit), it was like he was looking at her, but right through her.

She couldn’t believe what lightweights they were sending over from Oxford these days. Kenneth Hamilton was supposed to be a serious scholar, and his theory was supposed to provide a new way of looking at probability. But so far all she heard was him talking on his cell phone, and then after that a distracted lecture, as if he was still thinking about what he'd just heard on his phone. Madame Dupont wouldn't have allowed one of those things in her classroom. She would certainly not insult her audience by carrying on a private conversation at the front of the class. At the very least he could have the decency to pretend it wasn't a lover’s spat. And what was that accent, anyway? It sounded American.

☆

Martine was glowing inside. She knew it would put him off his game. The mention of Jean-Marc might even put him over the edge. Now, if she could just get him to step down from his pulpit and realize that his theories weren’t even convincing to the old geezers in his audience. Then she would be getting somewhere.

Who really cares if we can predict ranges of possibility? Or is it probability? One seemed as unlikely as the other. How can you live life while calculating the effect of this and that every twenty seconds? Surely for once he could just use his intuition to figure out what made sense. How else could she marry him?

☆

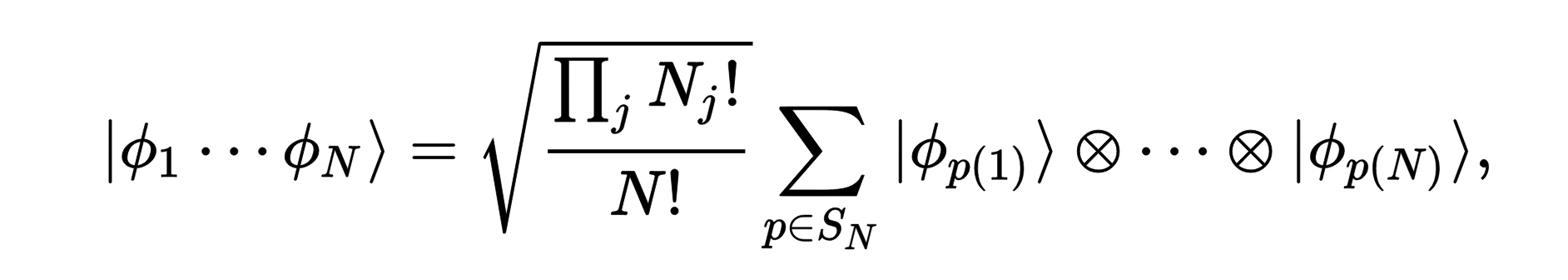

Madame Dupont wasn't impressed with the performance so far. Even if she could accept his odd premises. She could supply six equally probable premises. But then again, the way he spoke, those short sharp English cadences, reminded her of Conrad and of how often she was willing to accept his premises. Yet even if she accepted those of Professor Hamilton, there was still the fact that we can seldom see, and we can almost never accurately quantify, the variables. Pascal may have believed in mathematical certainties and axioms, but all of that was before Heisenberg and quantum mechanics. Before spectrographs and dark matter. Prediction was for charlatans and priests.

She couldn’t get the images out of her mind, the ones she saw just before she left her apartment. Even the Japanese, with their finely calibrated Seiko watches and terabyte robots, couldn’t see it coming. 8.9! However carefully they built, the buildings could all get swept away in trembling, flooding, radioisotopes, and fear. Le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis m'effraie. It brought her back, once again, to Pascal.

She thought to herself, the Earth trembles to remind us what we are.

When Kenneth finished his main argument, Madame Dupont put up her hand. “I find your theory very fascinante, professeur. But also very speculatif. Please excuse me for saying this, mais il me semble, it seems to me that you have made the fundamental error. You supposez that the essentialist systèmes operate sui generis, as if they were séparées one from the other. If you use the premise that individual volition is linked to some structure essentialiste, you must therefore consider that this essentialism has some agenda of its own. Can you, dans ce cas, séparez the particular intuition from the universal, the mythic intuition?”

The grey cloud shifted to the left side of the room as the heads of the audience turned in the direction of the elderly lady next to the exit in the front row. Even the octagenarian on the far side of the wide lecture hall, the one who never strayed from looking directly ahead of him, craned his rigid neck to see who was saying what many of them were also thinking. They were all so close to death that such thoughts were becoming second nature. That is, second nature in regard to the life to come, since the first nature of this life was now crumbling so completely.

Madame Dupont continued: “If the dictates of other systems were at work, with their own rules about kryptonite or qu'importe what mineral you imaginez it to be, who is to say that these other systèmes may not act similar to, or in correspondence with, the old mythic and religious systèmes of essentialism? I suspect that we may have made the full circle. From l'ancien myth of the soul infinie to the modern myth of la dimensionalité infinie of the soul.”

Kenneth looked down at his cellphone. It wasn’t blinking. But there was a bright blue stone on his finger. It seemed to pulse. Or was that his heart?

He realized he was in an auditorium, in front of an audience. Everybody was looking at their cellphones. He had no idea what the lady in the front row had just said. He thanked the lady for her observation and stepped down from the podium.

☆

Emerging into the courtyard, Kenneth ran into his colleague Stéphane.

“Ken! Did you hear about the earthquake in Japan? Holy Mother of God!”

It was at this moment, as the earth stood absolutely still beneath his feet, yet at the same time was rotating at 30 kilometres a second, that Kenneth resolved to ask Martine to marry him.

☆

Next: The Apple-Merchant of Babylon 1: Genesis