The Double Refuge 🎲 Almost Existential

The Permeable Self

Karma-Samsara & the Bug - Sartre, Camus, & Gnosticism - Petals - The Civic Architecture of Deities and Men - Romantic Revolt - Relativity

🎲

Karma-Samsara & the Bug

One of the hardest, sweetest truths is to realize that whatever your specific virtues or talents, you’re almost nothing standing beneath Shakespeare and the stars. The ego shrinks

till at last you reach the size of Kafka’s bug and scurry about your beetle business

until you’re old and grey and awed by the blades of grass

some greybeard cosmos sowed over your little grave

where you lie like one of Poe’s unhappy victims, waiting to be reborn

until finally you’re reincarnated in a caterpillar shape

inching your way toward the light

that glistens at the end of a dark wet bough

and take that daring leap

shaking your wings in the misty air

in the mountain ranges of Shan Shui

🎲

Sartre, Camus, & Gnosticism

Agnostics believe that while people may or may not have souls or essences, they most certainly are products of space and time, geography and history, nation and culture, family and peers. Their bodies, and the amalgam of thought and feeling within their bodies, may originate in divine or metaphysical worlds, yet they are most certainly created by the heavenly bodies that we call stars; by the solar system and this world; by the air, water, and earth; and by the flow of human cells, neurons, and genes over the face of the earth.

Hard-core existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) often see this realistic determinism as a limiting and deterministic affair. Curiously, Sartre's materialistic existentialism shares the spiritual, essentialist, gnostic conclusion that the world is a sort of prison and the body a sort of cage. Gnosticism is a multi-faceted strain of thinking, much of which is incompatible with present forms of Christianity, yet its dualism appears to have very deep roots, not only in early Christianity but also in Persian and Mesopotamian thought. Gnostics believe that there are two basic opposing aspects to the universe -- the spiritual and the physical -- and that our job is to find the primal essence, the inner spiritual truth or gnosis that lies trapped within (yet also beyond) the body. Sartre would of course reject the ideas of primal essence and gnosis, yet curiously, he ends up in a similar bind: the body and the world it perceives around it are alienated, set adrift in a world that doesn't make the right type of sense. While gnostics look at the world and their selves and see deep stains of sin, hard-core existentialists look at the world around them and see nauseating reflections of their selves.

🎲

Petals

In a Station of the Metro

The apparition of these faces in a crowd;

Petals on a wet black bough. (Ezra Pound, 1913)

Picking one God over another is like choosing between water and the sun:

both in their own way are supreme, and we can't live without either.

They give to us and we give nothing back.

Laozi says the Dao is like water,

and Saint Francis says that God is like the sun,

but they couldn't have thoughts these things without the earth,

its mineral and gem-like charms.

All three, a trinity of sorts, come together

in the petal that shoots from the black bough,

or in the apple that grows outward from the flower.

In Nausea, Sartre sees the black root of a chestnut tree

as if it were a snake: alien, almost evil.

The early Jews saw the snake as Satan,

offering knowledge as a curse.

The poet, on the other hand

refuses to pick between the water, earth, or sun

and sees only the petal

the form of the human face

hovering, like an apparition.

🎲

It seems to me that agnostic thinking resonates more with the softer-edged, more permeable version of existentialism offered by Albert Camus (1913-1960). Camus shares Sartre's deep skepticism about religion, God, and the spirit, yet he also seems to have an agnostic streak which allows him to remain open, or permeable to the possibilities that may well exist in a universe which existentialists cannot claim to fully understand. He's keenly aware of the doubtful nature of everything, including his own conclusions: “Les doutes, c’est ce que nous avons de plus intime” (Carnet); “Un homme est toujours la proie de ses vérités” (Le Mythe de Sisyphe) / Doubts, these are what we have that are most intimate"; "A man is always the prey of his truths." In his essay, "Existentialisme Entre Nature et Culture: Camus Contre Sartre," Pierre Zima argues that, "Contrary to Sartre, who argues for a subjective or aesthetic order that the subject imposes on the nature and universe of objects, Camus doesn't accept the dominance over nature implied by Sartre's rationalism." To exemplify this, Zima says that the following phrase (from Noces à Tipasa, 1938) is "inconcevable chez Sartre": "In the Spring, Tipasa is inhabited by the gods, and the gods speak in the sunlight and in the smell of absinthe” (trans. RYC).

In Doctors of Revolt I follow up on some of the other ideas in Zima's essay. Here, I want to explore several more similarities and differences between existentialists, essentialists, and agnostics. I also want to pick up on the theme of revolt by referring to

🎲

The Civic Architecture of Deities and Men

Existentialists and hard-core essentialists both aim to escape their negative states: existentialists try to escape the nausea (to use Sartre's term) of seeing everything in terms of their limited selves by engaging in the world; gnostics try to open the door of the cage and transform the prison into a city of God (to use Saint Augustine's term). Existentialists accept the limits of the physical world and try to find their freedom within it. Essentialists on the other hand reject the physical limits -- both in terms of space and time.

Essentialists superimpose spiritual space over physical space. The best example of this is Augustine's city of God, yet it's a basic gnostic, platonic and Christian notion that there's an ideal spiritual world and a realistic physical world. This might be seen as an adjunct to the third dimension of space, or as part of the space-time of a spiritual fifth dimension.

Essentialists also extend human time, believing that the soul exists within a long timeframe established by the infinity of God. This might be seen as an adjunct to the fourth dimension of time, or it can be seen as part of the space-time of a spiritual fifth dimension.

The soul joins other souls in Heaven or some other metaphysical realm, and in some cases even the human body slides beyond this life into the next, where it's resurrected. Or, if essentialists believe in reincarnation, the soul takes another body, and the process is considerably more complicated -- at least in Hinduism and Buddhism: the soul may inhabit hundreds of new bodies, the world goes up and down in enormous cycles of hundreds of thousands of years (called yugas), and the universe itself may be destroyed and re-created literally ad infinitum or to infinity. Whether in resurrection or reincarnation, the soul of the essentialist evaporates from this world of time and space and re-condenses in another realm. While the existentialist may see this state as lacking in free will -- since the higher or greater realm determines the lower – it’s a type of free will that essentialists are more than willing to forego.

🎲

Romantic Revolt

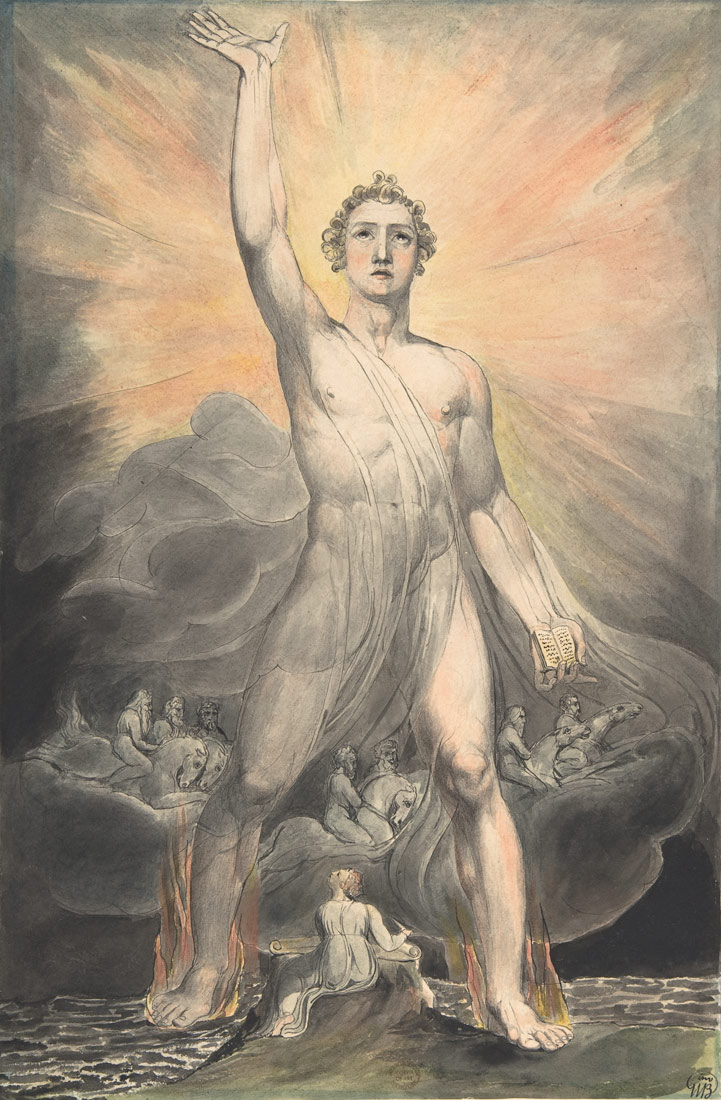

The poetry and visual art of William Blake (1757-1827) expresses the circular yet powerful essentialist dynamic in which the spirit revolts against the body and the senses that limit the visions of infinity required by the infinity of God and spirit. In the first image below, Blake depicts Isaac Newton locked in the material world: he appears to be deep at the bottom of the sea, and his eyes are focused narrowly on the geometry of his mental constructions. This image of a limiting perception contrasts sharply with the second image, in which the vision of the spiritual man is cast far and wide. His whole body acts as a conduit for divine energies -- a state of vision which transcends the dichotomous spirit/body division of the gnostic. Together these two images illustrate Blake's revolt against what he calls mind-forged manacles, his Romantic notion that Imagination (with a capital I) is the real and eternal world of which this vegetable universe is but a faint shadow, and his belief that If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.

Blake's Newton. Monotype, 1805; Blake's Angel of the Revelation (Book of Revelation, Chapter 10). Watercolour, c.1805.

Blake is the most mystical and obscure of the English Romantic poets, and at times he appears to attack the notion of rationality. Yet his system of liberation is driven by words and systems of his own -- consonant with his view that one must create one's own system or be enslaved by someone else's system. The second-generation of Romantic poets (Byron, Keats, and Shelley) are far more positive toward Enlightenment rationality, yet their poetry also contains various forms of revolt from the material world. I see them as the first fully Modern generation, that is, the first generation to accept the reason, science, and technology of the late 18th Century and yet to attempt to recuperate the emotion and spirituality occluded by the powerful combination of science, empirical philosophy, and a brave, new, and at times frightening mechanical world.

For both the existentialist and the essentialist a transformative vision is involved. For the essentialist, the world becomes other, becomes something more than what it was. For the existentialist, the world stays the same, but the attitude towards it becomes different: ideally, the alienated self transforms its feelings of angst and absurdity into constructive engagement. Sartre and Camus agree on the need for transformation, yet while Sartre emphasizes rational revolt and dominance over nature, Camus seems more of a Romantic in that he looks for liberation in a combination of rationality and quasi-mystical annihilation of the self; in a fusion of accepted Enlightenment rationality, and immersion in in reason and the capitalized forces of human Imagination and immersion in the hidden depths of Nature.

The essentialist would say that the existentialist is still trapped in the world as it was, while the existentialist would say that the essentialist is detached from the world as it is. The agnostic entertains both these views, adding to their was and is a variety of might bes.

Agnostics recommend a world of permeability, where one state of being (in the body) opens to another (in the body politic) and where this process reverses itself -- from the body politic back to the body, which is our natural home while we're alive. Looking at this process within a larger time-frame, our primary and ultimate position lies within the greater world -- the world of dust, trees, and ashes -- which condenses to form our human bodies, which live out their lives (venturing out to the body politic yet always coming back to the body), after which our bodies go back to the larger universe. After this final transformation, the process, or any future movement, is unknown. All that we can see is the ashes and dust which fall back into the soil, to rise again as trees and birds, or to stay in the earth, a layer of condensed sediment locked in patterns for a billion years.

The Daoist writer Zhuangzi put this imaginatively when he wrote that we may be dreaming that we are human when we are in fact butterflies, and when he comments on the uncertainty of our ultimate destination:

🎲

Relativity

The meaning of life, if there is such a thing, has everything — and nothing — to do with you.

Your self is the funnel for everything. It takes in all that you've ever known, ever been, ever imagined yourself to be, and everything that you've ever imagined the universe to be. To say therefore that the great and small mechanics of reality have nothing to do with you is a complete falsehood as concerns your experience and understanding.

Yet this understanding can also see that the self is microscopic in the larger mechanics of space (from your neighbourhood to your city, country, world, solar system, galaxy, galaxy cluster, and the outer reaches of the universe) and in the larger mechanics of time (from your 80-odd years to the Age in which you live, to life on Earth, to the lifespan of Earth, all the way to the Big Bang).

It's all meaningless. And it's all completely meaningful.

To accept this duality of relevance and irrelevance is to understand relativity itself. Not the abstract, faraway physics of Einstein, but the concrete, close-at-hand physics of your life, your self.

Given that we're continually finding ourselves -- and continually losing ourselves -- between the infinitely small and the infinitely large, does it make sense to hold on to fixed ideas about what we really know? Does it make sense -- either practically or theoretically -- to hold on to fixed ideas about the universe or eternal truth?

🎲

Next: Starbucking