The Double Refuge 🦖 At The Wild & Fog

A Passage to Forster

19 Going on 20 - 1924: A Passage to India - The Transcendence of Time

🦖

19 Going on 20

A society is fortunate if, in modernizing an outdated system, it has at hand a new, overarching system — in this case liberal democracy — which can accommodate new facts and realities while saving or recuperating helpful things that the old system contained. Otherwise, the society experiences revolution without direction, as in the French madness of 1793. England was more fortunate than France since it benefitted from a gradual shift from conservative to liberal politics after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, where parliament secured the upper hand in sharing power with the monarchy. In the 17th and 18th centuries it moved from Hobbes’ authoritarian vision to Locke’s democratic one, although power remained in the hands of a very few wealthy men.

In the 19th century English society goes from a very limited conservative democracy to an early version of a liberal democracy, one that advanced the abolition of slavery world-wide and exported the idea of universal suffrage. It’s partly for this reason that I include Forster’s novel about early 20th century India: at this time Britain was in the midst of giving women the vote, yet it was still to give India their own parliament. The liberal agenda wouldn’t be complete until 1947, when England releases its control of the Indian subcontinent, and until the 1960s, when it releases its control over large chunks of Africa.

Many religious and philosophical systems are burdened with the past. They must blend what’s worth keeping and winnow out what limits their applicability, authority, and development. Agnosticism is lucky in this regard, given that its birth is very recent — largely in the years after Darwin articulated what we might call the law of evolution (theory is far too tentative a word for such a well-documented explanation).

There are many ways that agnosticism parallels recent history (not least of these in the realms of science, phenomenology, and existentialism), yet here I’d underscore the importance of politics. If people are to think freely about religion and atheism they need the political freedom to read and write what they want to. Cultural advancements come from interchange of knowledge, ideas, and techniques, and if people aren’t free to exchange these, progress is bound to be stunted. If you aren’t allowed to question openly, and if you are coerced privately, then it’s difficult to explore in the unbounded manner required for agnosticism.

The advances of liberal democracy come hand in hand with the development of 19th and 20th century agnosticism, which might be defined as an overarching epistemological system which accommodates changes in both religion and science. In this sense I see Dickens’ giant lizard as a harbinger of Darwin’s evolution, of Huxley’s agnosticism, and of the demise of antiquated illiberal institutions. Dickens’ image challenges the Divine Plan Pope celebrates, and it also anticipates the perspective of Forster, who expresses a Modern alienated sensibility, yet also a modern agnosticism which cherishes the exploration of both science and religion.

🦖

1924: A Passage to India

Forster’s A Passage to India was published several decades after Ramón y Cajal identified the neuron in 1888 and roughly around the time genetics and DNA was explored (from Mendel in 1865 to Watson and Crick in 1953). Perhaps most felicitously, Passage was published the same year Hubble demonstrated the immensity of the universe. In this sense his novel might be seen as a take on Whitman and the type of open Transcendentalist thinking that led him to write the long poem Passage to India, and to declare in Song of Myself, “Unscrew the locks from the doors! Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!”

🦖

Forster wasn’t puzzled about many of the scientific things that puzzled Pope and Dickens, yet the fundamental questions of soul and deity were still infinitely debatable. Forster knew that the Bible couldn’t be understood literally, at least not by people who insisted on rational, historical, verifiable explanations. He knew that the scientific explanation initiated by Copernicus, Hutton, Lamarck, and Darwin was so extensive that it overwhelmed the older religious explanations which lacked historical accuracy and detailed information about the structure and functioning of the universe. Yet still, religious questions remained, especially about those religions that weren’t hindered by literal or historical claims.

This is perhaps why he portrays Hinduism in the novel in both a skeptical and mystical way — in brief in an agnostic way. Religion isn’t the implicit answer to everything, as it is in Pope’s Essay on Man. Nor is it a system that’s implicitly true yet also an implicit parallel to outdated and irrational systems, as in Bleak House.

Rather, Forster’s Hinduism is a detached entity, unburdened by history, dogma, or social constraint. It allows him to look into the questions of theology without the baggage that comes from the type of deeper personal, psychological, sociological, and historical understanding he has of Christianity.

I should note that Indian writings of that time — such as Premchand’s “Deliverance” (1931) and Anand’s Untouchable (1935) — didn’t separate religious idealism from religious practice. In other words, they didn’t let Hinduism off so lightly. To the contrary, they drilled away at the injustice of caste and at the elite indifference of brahmins. Although in this sense Forster’s Hinduism is a sort of fantasy Hinduism, it nevertheless fits the bill for his agnostic exploration of religion unburdened by the type of literalism and historical baggage we find in Abrahamic religions. Forster’s Hinduism allows him to explore the claims of transcendental or spiritual meaning without the politics, sociology, or history.

A Passage to India (1924) operates less ambiguously on the level of race, politics, and nationality. Although Forster doesn’t even mention the Amritsar Massacre of 1919 in the novel (five years prior to its publication), he nevertheless pushes liberalism — with its respect for personal and national sovereignty — into a global forum, challenging the assumptions of the British Empire. Through his characters of Fielding, Aziz, and Mrs. Moore, Forster argues that it’s not only White European Males who should get to control their own destiny. While Dickens mocks Miss Wisk’s pre-Suffragette feminism, Forster suggests that Mrs Moore and Adela aren’t nearly as doddering or frivolous as they first appear.

I should note more of the historical context here: A Passage to India is published many decades after Mill’s 1869 tract The Subjection of Women, and exactly between the 1918 and 1928 Acts which ensured the franchise of all women in the UK. While Dickens mocks Mrs Jellyby’s obsession with Africa, Forster shines the spotlight on the inconsistent application of English democracy abroad by championing equality with Aziz and the other Indians who Fielding befriends. While Forster is in sympathy with his female characters, he isn’t in advance of them politically. Yet he is in advance of his characters in the realm of global politics and Empire, since the equality he suggests isn’t realized until the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947.

🦖

The Transcendence of Time

I’d argue that Forster is also in a philosophic vanguard of sorts: he questions the traditional civilizational timeline by conflating — and thus transcending — different time periods. In his Aspects of the Novel (1927) he rejects “fiction by periods” and “that demon of chronology.” He says that we should see writers not as products of time periods, but as artists

at work together in a circular room. I shall not mention their names until we have heard their words, because a name brings associations with it, dates, gossip, all the furniture of the method we are discarding. (Aspects of the Novel, 1927)

Forster also says, “we cannot consider fiction by periods, we must not contemplate the stream of time.” In a later chapter he even looks down at the sequences of time that make up every story:

The life in time is so obviously base and inferior that the question naturally occurs: cannot the novelist abolish it from his work, even as a mystic asserts he has abolished it from his experience, and install its radiant alternative alone?

Forster is writing strategically here, for on the next page he admits that “time-sequence cannot be destroyed without carrying in its ruin all that should have taken its place; the novel that would express values only becomes unintelligible and therefore valueless.”

He writes playfully when he rejects looking at literature according to time period, yet for the sake of argument let’s take him at his word. Let’s look at this “stream of time,” as it goes from Babylon and Jerusalem to Athens, from Athens to Rome, and from Rome to Paris and London. Let’s look at its sources of mountain rain and aquifer, at its slow meander and its violent rapids, at its merging and diverging, and at its final flow into lake, delta, and ocean. Contemplating the stream of time in this way allows us to consider fiction by periods without being boxed in. The river is an extremely helpful metaphor and periods of time are all we’ve got.

🦖

Before stepping into my argument, I’d like to take a quick irreverent side-trip into Forster’s subtle comedy of circular rooms and furniture. What exactly does the author of A Passage to India mean by “the furniture of the method we are discarding”? What is “the method” which employs furniture? Is this method the way furniture is designed, or is it the way furniture matches the design of the room? Are we to match the chairs with the portal and balustrade (if the room indeed has a portal and a balustrade)? If this is the case, we need to know if the chairs are made of wood or iron. Are they lacquered or painted, curved or straight? Is the room really circular, or was that just a fictional room, one we speculate about while we sit in a real chair in a real room, which 99 times out of 100 is square? And if Forster’s determined to discard the furniture, are we to write sitting on the floor?

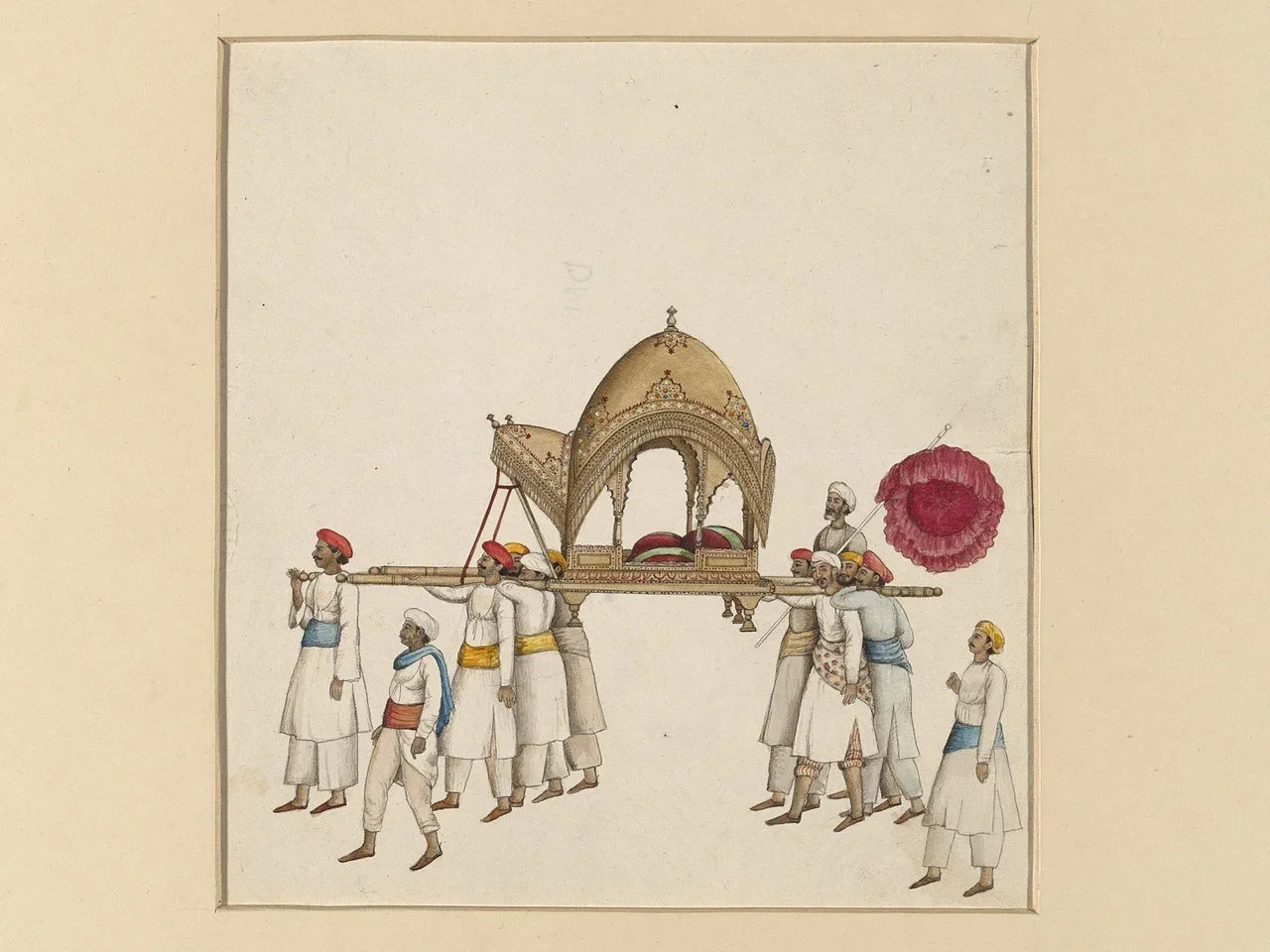

What does Forster have against furniture, anyway? Is he thinking about Danish tables or Ikea recliners? Does he have something against Danes and Swedes? Given his shameless Indophilia, perhaps he’d prefer to sit in Bahadur Shah’s sedan chair:

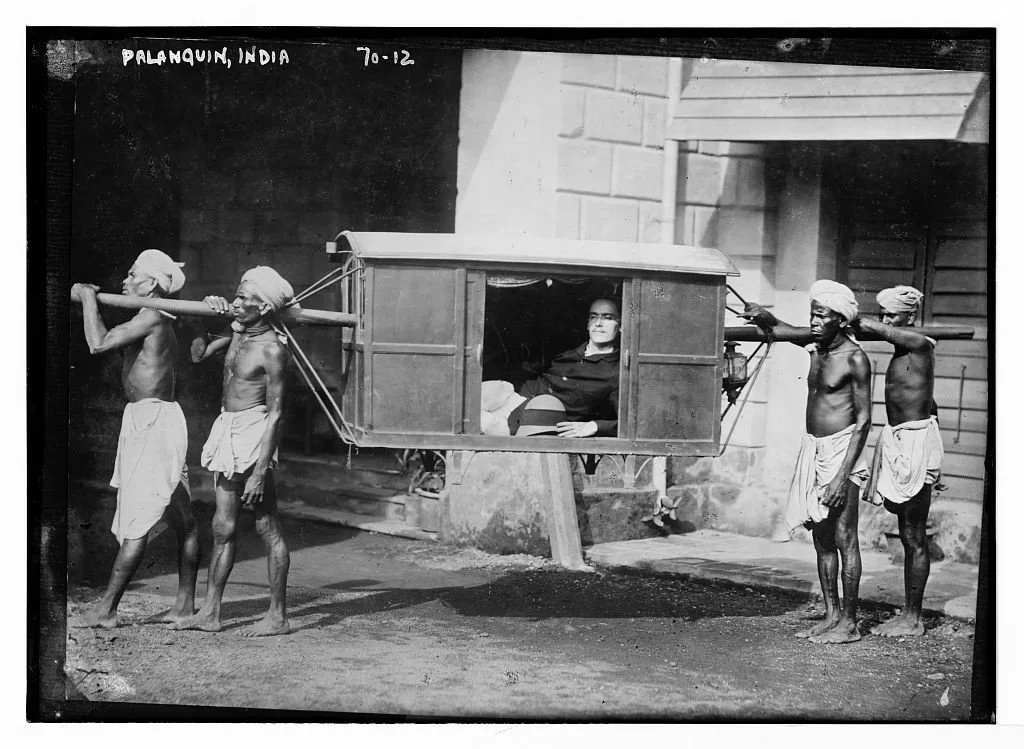

Or perhaps he’d feel more comfortable, less like an Angrez sahib, in a more humble sedan chair in a less famous princely state…

I suspect Forster would be happy in this sedan chair, having gone back and forth to India, after having followed Achilles closely as he made his way with the Idalian birds across the Aegean, and then taken a longer journey (on his imperial liner) through the Suez and into the Arabian Sea. Into the Indian Ocean, to the dark-skinned men with their thick beards, or with their clean-shaven faces that show yet traces of black stubble beneath.

There, on the open seas of Arabian and India he’d no longer shudder at the thought of Bloomsbury coffee spoons with their dribbles of cream, or at the sight of the kohl-less eyes of the ladies that fix him in a formulated phrase. He’d no longer find himself formulated, sprawling on a pin, and wriggling on the wall.

Even though the Amritsar Massacre of 1919 was only a few years ago, Forster would still feel like he was back in his element, a sympathetic sahib carried through the streets by dark and muscled men, ready to take on the British Raj and all the tight-assed rules of their club.

The bearers of his sedan chair turn right, go down a back alley, along an old fort wall and into a private entrance. They then carry him, sans sedan, sans dhoti and sans kaupinam, up to the Maharaja’s chamber overlooking the dazzling city of Agrabah…

But are sedan chairs really furniture? Or are they some type of transportation vehicle?

🦖

The further back in time we go, and the further afield we roam, the more we’re tempted to go further. Not to find something strange and alien, but to test Forster’s notion that writers transcend time and place. Do they in fact write in the same room — rather than, say, a condo in 2025, an Indian sedan in 1921, an attic in 1601, and 1001 locations upstream in times past?

While Forster may be correct when he says that writers “work together in the same circular room,” his comments about rivers and time-periods aren’t so easy to believe. One moment he says “we must not contemplate the stream of time” and the next he contemplates the applicability of different time-frames:

Four thousand, fourteen thousand years might give us pause, but four hundred years is nothing in the life of our race, and does not allow room for any measurable change.

He then supplies detailed examples of how writers change very little from century to century. And yet in doing this he misses two crucial points: 1. the closer we get to the present, the more rapid the change; 2. the further back we go in time, the more we see the most enduring changes. 400 years ago people had no clue about laws of gravity, galaxies, or quantum fields. In 1821 Keats died of tuberculosis, which back then was supposedly caused by masturbation and cured by leeches. If we go back 4000 years to Mesopotamia we find similar misconceptions, yet we also find the invention of numbers and letters, legal systems and organized warfare, religious systems and astronomy. We see more clearly how deeply the Ancient past is still part of our present lives.

Mesopotamia and its cuneiform script are why I type this paper, right now. Fingers over keyboard, I imagine that somewhere in Forster’s circular room a scribe is getting out his moist clay tablet and making cuneiform strokes with his stylus, writing about the rivers of time.

What unites us is far older than 14,000 years. Whether our past is in broken tablets or fragments of dinosaur bones, it still comes from the same ancient DNA. It’s all around us, deep in our bones and up in the sky, with the birds whose light bones retain the largest share of the ancient genetic codes of Crocodylia and Tyrannosaurus Rex. How much more then do we share with the first great civilizations of Sumer and Akkad!

Although The Epic of Gilgamesh began in the 3rd millennium BC and reached its classic form by around 1200 BC, we already see in it our own ideas about justice, myth, iconoclasm, civilization, love, jealousy, honour, war, rebellion, angst, existentialism, and the afterlife. If the word Classical means what creates the foundations of civilization, then Gilgamesh is both an Ancient World text and a Classical text par excellence.

The clay tablets of Mesopotamia were illegible for ay least 2000 years, from several centuries before Christ to the 19th Century. The civilizations of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria thus became the underground rivers of our past. In some ways this is similar to the way that the Saraswati River was home to the Vedic poets in India, yet today the river is nowhere to be seen. To Hindus however the stream of water never went elsewhere completely; the script used to write Sanskrit (Devanagari) is used today for Hindi. The Saraswati river may flow underground, yet it surfaces at Prayagraj, where it meets the Yamuna and the Ganges. The river is identified with Saraswati, both the ancient river and the Goddess of language, art, and literature.

The clay tablets of Mesopotamia resurfaced in the 19th century, speaking with fantastical eloquence after two thousand years. The eloquence was also explosive when George Smith first read the passages of Gilgamesh to the Royal Society in 1872. The passage came from the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC, and was about a man called Utnapishtim, who was told by a god that the world was about to be destroyed by flood. Utnapishtim built an ark, so many cubits by so many cubits, waited till the rain and the god’s anger had subsided, send out a bird, land on a mountain, praise the powers that be, etc. You know the story.

Before Noah was Utnapishtim, and before clay tablets was the spoken word, human sound, gesture, and the song of birds. Going back far enough we find our old friend Tyrannosaurus Rex, who proves to us, with his very bones nestled in stone and dust, the deeply-coded reality of our evolution. Amino acids became strands, neurons became mental and physical capabilities. Then a great disruption occurred. Cataclysm and extinction for Old T. Rex. But the species that survived continued to evolve. Eventually, the same encoded DNA created an upwardly mobile species with larger brains and wattle homes and irrigation channels, temples and libraries, senate chambers and space ships.

Old Rex shows us that we’re not just mortal as individuals, but also as a species. We’re here one period of a hundred million years, and gone the next. Forster admits as much in Chapter 14 of A Passage to India. He notes that the traditional myths we ascribe to the world (which I hasten to add appear between 400 and 4000 years ago!) are relatively new, compared to changing riverbeds:

The Ganges, though flowing from the foot of Vishnu and through Siva’s hair, is not an ancient stream. Geology, looking further than religion, knows of a time when neither the river nor the Himalayas that nourished it existed, and an ocean flowed over the holy places of Hindustan.

Forster may be right about the community of writers. He may even be right that writers transcend their own time period. But this doesn’t mean that time periods aren’t helpful. If we see a time period as a box, separate from the boxes beside it, then a time period confines. Yet if we see a time period as a portion of a river, then we have a hard time keeping the water in the box.

🦖

Rivers and time periods aren’t the problem; fixed views of them are. We can see a particular river as sacred — the Bible’s Jordan, Rome’s Tiber, or the Hindu’s Ganges — but we don’t need to be blind to all others. We can imagine that rivers mean the same abstract things: the inspiration of the artist on the banks of the Tiber or Saraswati; the flow of time past Babylon or London, the constant change of Heraclitus or Buddha.

We can look at the river as a hydrologist, seeing its sources, its present constituents, and its destination. We can look at the river as a botanist, noting that one stretch is mired in mangrove roots and sea water while another bakes in the hot desert air. Another is surrounded by hill and mountain, while yet another has disappeared in the underground of the hydrologist and his water tables.

We can look at the river like Mark Twain’s river pilot on the Mississippi, who sees ripples as signs of underwater danger: rocks and snags we need to steer clear of if we are to safeguard the lives of the passengers, who overlook the hazards of the ripple. The passengers see the ripples as gold and pink in the sunset, all the while wondering what’s for dinner.

Moreover, it’s natural for us to think in terms of specific periods of time. Time periods may be arbitrary, but so are we. We are born in one year and we die in another. The more we look into this brief timeline, the more we see it as arbitrary, open to interpretation, ultimately mysterious. What determines the two points? Destiny and the astrology of stars? Previous actions tossed into the recycling bin of reincarnation? Blind causes and effects of Nature and survival? An individualized personal Plan devised by an omniscient God? Who knows? And yet we do know one thing: everything that we experience lies between the point of our birth and the point of our death. Everything else is for everybody else to determine.

🦖

In examining the foundations of culture, it’s best to keep time periods elastic, and to follow the rivers to their sources underground. Going backward in the letters of time, we reach a point where the river seems to disappear: the texts that we can see are in Phoenician or Aramaic, Hebrew or Greek. The ones we can’t read are in broken clay tablets, in a cuneiform script that dominated the civilized world for three thousand years yet are now alien to most of us. They have become illegible to our human brains and invisible to our naked eyes.

Yet the geology and hydrology know the source is there, as does archaeology and the philology. They know that our DNA and our instincts come from reptiles and apes. They know that much of our present world, including our Western literature and religion, comes from Nineveh, Babylon, and Uruk. They know that The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Code of Hammurabi run deeper than the new-fangled stories and laws of Abraham and his tribe.

While we may have been brought up to believe that the Bible is inextricably wedded to our cultural identity, I’d argue that the Virgin Mother of God is stranger to us than Ishtar, with her seductions and jealousies. Abraham and Moses are stranger to us than Gilgamesh, with his egotism and lust, his desire for power and glory, and his angst at the realization that there’s no afterlife world in which he’ll reunite with his beloved Enkidu. In contrast, how many of us live our lives like a Jewish patriarch, negotiating our collective contract with God? How often do we worry about a promised land for our tribe? When we’re hungry, do we worry about what and when we’re supposed to eat? When we want to buy an iPhone or a new car, do we worry about the Golden Calf?

The idea that Western culture starts in Greece is a convenient one to be sure. Greece is the meeting place of 1. Paul’s Christianity and 2. the literature and civilizations of Homer, Heraclitus, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Sophocles, Virgil, Ovid, Seneca, and Aurelius. It’s perhaps no coincidence that the clearest articulation of Christian theology appears in the chapter of the Bible called “Romans.”

But this is a bizarre take on the foundations of Western culture. Wouldn’t it make more sense to start with the Mesopotamian invention of numbers, mathematics, and writing, with the earliest epic Gilgamesh, and with the Mesopotamian city-states that gave birth to complex trade, civic organization, organized religion, legal codes, warfare, etc.?

🦖

The past, which no one owns, makes us what we are. It’s all a historical line, a river in time, whether of intellectual argument or practical life. To us, the river seems to move westward from the Middle East and northwestward from the Aegean, then the power of industrialized numbers and letters presses southward and eastward, back to its deepest origins.

For culture, as for each of us, the argument is detailed and complex. Yet for everyone it goes from alpha to omega, from the beginning to the end. From where we start to where we end, whether in folded diapers or paper folio. With the proviso that for culture — deathless in clay, paper or screen — there is in fact no beginning and no end. All we have are fables, fabulous and real.