The Great Game 🎲 Fallar Discordia

In the Forests of the Night

🎲

The flight from Mount Voolkan to the Student Quarter took about ten minutes. As he flew, Farenn saw the water spilling over the ring of foothills and into the canals. The people living on the banks of the canals were used to the flood, so within half an hour they were already putting up their floorboards on stilts in the overflow canals (or “trenches”). They’d already started arguing with their neighbours, who referred to them as something like “those fucking Gypsies.”

Back in his peaceful penthouse, Farenn looked down at his fractal orb. Looking at this floating 3-D version of the cosmos, he simply couldn’t believe the complexity of it all. How could all of these worlds fit together? What mechanism allowed them to evolve with such infinite design? Was it just evolution? And was the cosmos therefore indifferent to right and wrong, good and evil? He remembered the line from William Blake: “What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?” Had some distant Power, some invisible Hand or Eye created it all? Or were the philosophers right when they argued that it was all Chance, all a giant Game, the outcome of which was always up for grabs?

Because Farenn lived at the centre (or some would say the epicentre) of the Black Pulse universe, and because he was an ambassador, he knew a thing or two about chaos and the Ferridian Priests. Farenn had seen these Priests in their dark gowns up close, with all their flaws and petty jealousies. He’d seen the way they lorded it over everyone in the capital. They treated everyone, even the High Ministers of State, like rats from the trenches of Datchau. In principle, the Priests were subordinate to the Ministers, but what did the Priests care for institutions or government? They worked instead on people’s superstitions, insinuating at every turn that they had some sort of occult power, without which the Fallarian Dominion would come crumbling to the ground.

Farenn had spent most of his life in the Student Quarter (formally called the University District), which lay between the University and the Datchau slum. His parents wrote scholarly articles for Kraslikan news sites, in an attempt to make the rest of the cosmos understand the Fallarians. There were far too many misconceptions, largely as a result of the Ferridian Priests.

Farenn’s library was the largest room in the penthouse, and Farenn loved to read the books in their primitive tangible form. Of course, he used his fractal orb, and therefore had a trillion volumes at the tips of his fingers. Yet there was nothing he loved more than to sit in his sunken armchair in the corner of the library, a good reading light above him on his left, his fractal orb hovering above him on his right, a strong coffee on the table beside him, and some rare old book between his hands.

Farenn was also what you might call an Anglophile. He loved all the great writers of the cosmos, but he was most fond of the writers from Earth — and from England in particular. The English writers took great flights of imagination, yet they always landed their craft on solid ground. In this way, they were similar to Fallarians. While a Vicinese writer would leave his spaceship rocketing through unknown heavens, and while a Blue Dream writer would find names for each of these unknown heavens, a Fallarian writer would sooner or later ask how much fuel was left in the tank.

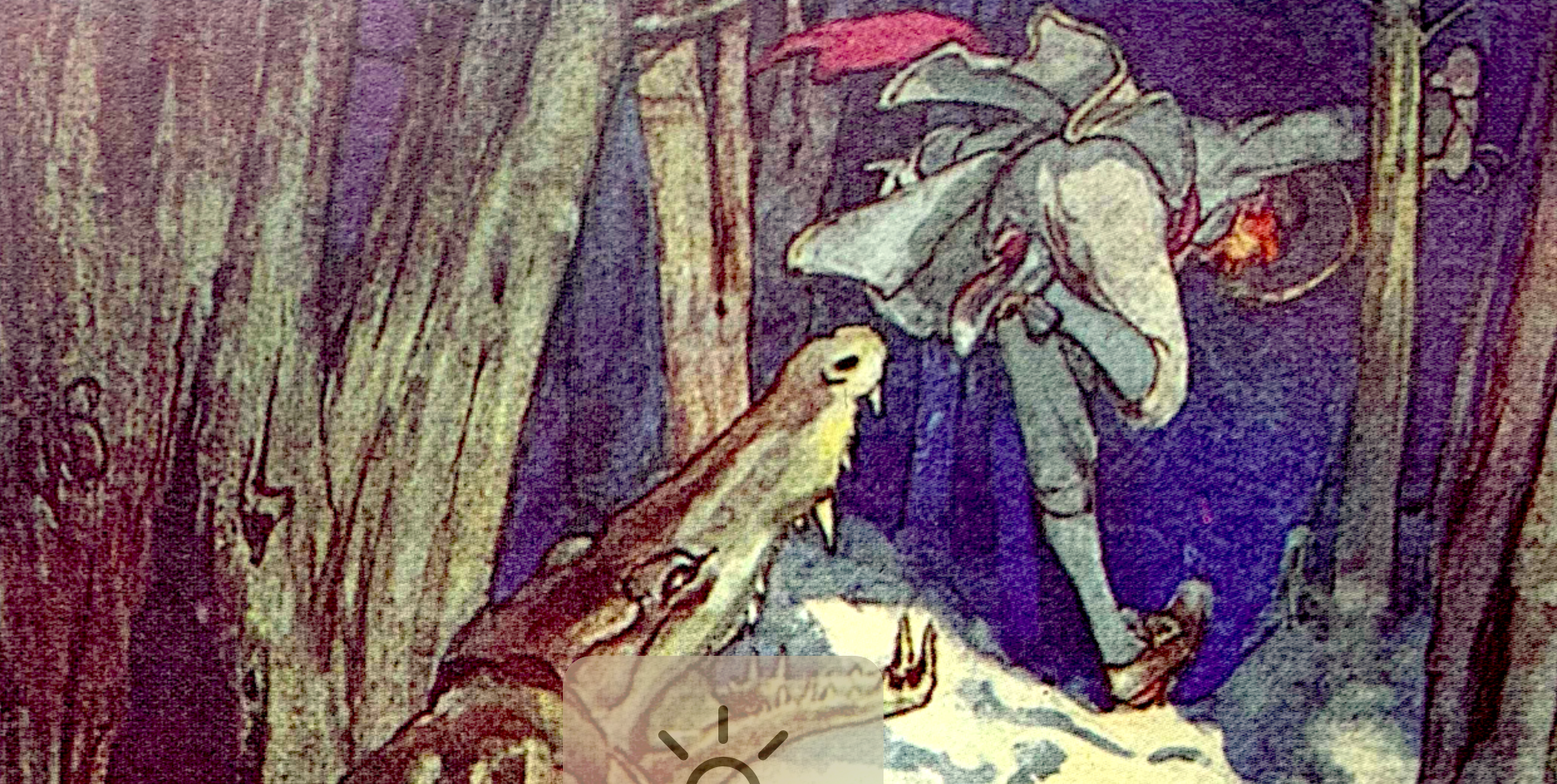

The Vicinese and Blue Dreamers were like Edgar Allen Poe and H.P. Lovecraft, whose ships took such long and fantastic flights that they eventually crashed on some forlorn icy realm. There, amphibious monsters hiding in the swamps eventually sniffed them out and tracked them to some gruesome end.

Farenn was quick to note that Poe and Lovecraft were American, not English. His friends at school hardly knew the difference, and they told him that he ought to read Fallarian literature, or at least the literature of the Yellow Sky or the Frozen Skiff. Yet Farenn would tell them that he had his reasons.

Sometimes he even hinted to his friends that his reasons were occult, and were in some way related to the Soul Star. But actually, he just liked the English writers. Shakespeare, Chaucer, Swift, Keats, Byron, Dickens, and Forster, they were all so fantastical and yet all so grounded. For instance, they all looked for truth, yet they never forgot the most fundamental truth: truth comes in many forms, and it’s most often a function of time and place.

Even Milton, who imagined he’d found the Greatest Truth, had principles that led elsewhere: his Christian Truth didn’t trump his belief that we should read permissively, that we should understand all sorts of evil things, so that we might better understand the meaning of holiness. Farenn spied a problem here, a problem which any Ferridian Priest would be quick to point out: if we read all manner of evil things, we’ll think all manner of evil thoughts. And then, inevitably, we’ll do all manner of evil things.

Farenn loved the poetry of John Keats and the Romantics, yet he struggled with William Blake, who Byron called that madman. In his longer works, Blake created worlds so convoluted that most people gave up on him. If these works were grounded, they were grounded somewhere else. But Blake could also be clear and simple — for instance, “Opposition is true friendship,” “The lust of the goat is the glory of God.” In his short poems, Blake used simple language and dealt with apparently simple concepts like love, meaning, and charity. Yet what difficult questions he asked in such simple words! With Blake echoing through his mind, Farenn asked himself, Who created this awesome cosmos, when “the stars threw down their spears / And watered heaven with their tears?” Who created the lamb? Did this Force also create the tiger and the Ferridian Priest?

Farenn looked out the window and saw the black and infinite sky. He imagined the ten trillion galaxies of the Black Pulse, sextillions of parsecs wide. He then looked down into his fractal orb. Within that Fallarian star-ocean of Terror, Lightning, and Light, he saw the red eyes of the Ferridian Priests. He asked himself, Who created the tiger, with his eyes “burning bright, / In the forests of the night? … In what distant deeps or skies. / Burnt the fire of thine eyes?”

Farenn looked out his window and then back down at his fractal orb. Perhaps the most striking thing about the cosmos wasn’t its perfect ovoid form, or its perfect symmetry — with the Black Pulse at one end and the Purple Pulse at the other. Perhaps its most striking feature was its lack of purity.

Everything from language to genetics was a mix. The reason this was striking was that on the surface it seemed the exact opposite. Theoretically, the Vicinese and Fallarians each have their place firmly on the moral spectrum: the Vicinese were angelic and the Fallarians were demonic. Yet in practice the spectrum collapsed into a line, the line curved into a ball, and the ball rolled away. The proof of this was that the supposedly angelic Vicinese had some of the dirtiest, rottenest scoundrels that ever walked on two feet. Likewise, the supposedly demonic Fallarians had some of the most valiant heroes that ever lifted into the air.

This same mix was found in languages and cultures throughout the Kraslika. The Vicinese vaunted their purity and wrote long treatises on the sub-dialects of Tuscany, and yet only half od their language was Vicinese. A quarter of their words were Fallarian. Likewise, a quarter of Fallarian words were Vicinese. The other quarter of their languages were an inextricable mix of Slavic, Turkic, Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Quechua, Guarani, Swahili, Malay, Mandarin, Korean, and Japanese.

Farenn had just started reading E.M. Forster’s book on the novel, and was trying to imagine, as Forster imagines, a circular room filled with writers from everywhere. Each writer is writing in their own language and special dialect. Each is writing about their way of life, their thinking, and their civilization. Each thinks their language is precisely what’s needed to get at the truth of things.

He imagined John Keats in that room. Keats catches a vague melody floating through the air, and imagines a place beyond hatred and pain. He feels the dull numbness paining his sense, as though of hemlock he had drunk, or emptied some dull opiate to the drains one minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk. He imagines that this opiate blots out his painful world, and offers him an alternative. Yet he still feels the gulf between that better place and where he is. He imagines a bird flying into the forest. O for a beaker full of the warm South, with beaded bubbles winking at the brim! Oh, that I might drink, and leave the world unseen, and with thee fade away into the forest dim!

He looks up from his pen and paper, and notices that the other writers also have pens in their hands. All of them are writing on paper, and everything they write about seems to be the truth, a final capping of their finest brains.

From somewhere outside the circular room, beyond and perhaps above, he hears the song of a nightingale.