The Double Refuge ✝︎ Saint Francis

Pascal’s Wager 1

Pensées

Spin - Context

✝︎

Spin

In his Thoughts / Pensées, Blaise Pascal (1623-62) makes an argument that’s often referred to as Pascal's wager.

Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God exists. Let us estimate these two cases: if you win, you win everything; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation, that He exists.

I think Pascal’s wager is provocative and influential, yet ultimately a limited — and limiting — proposition. In the wager, Pascal encourages a belief which he sees as opening up the meaning of the universe, yet I’d argue that he also unintentionally encourages a stark, unhelpful division between believers and unbelievers.

The wager gives a mathematical, probability-based argument for believing in an idealistic vision of this life and the afterlife, rather than believing that our lives are finite and determined by random and mechanical forces and factors. Yet Pascal’s simple logic has several drawbacks — not from the universal hope of universal benevolence and eternal life, but from the specific and extreme outcomes he suggests if one doesn’t choose belief.

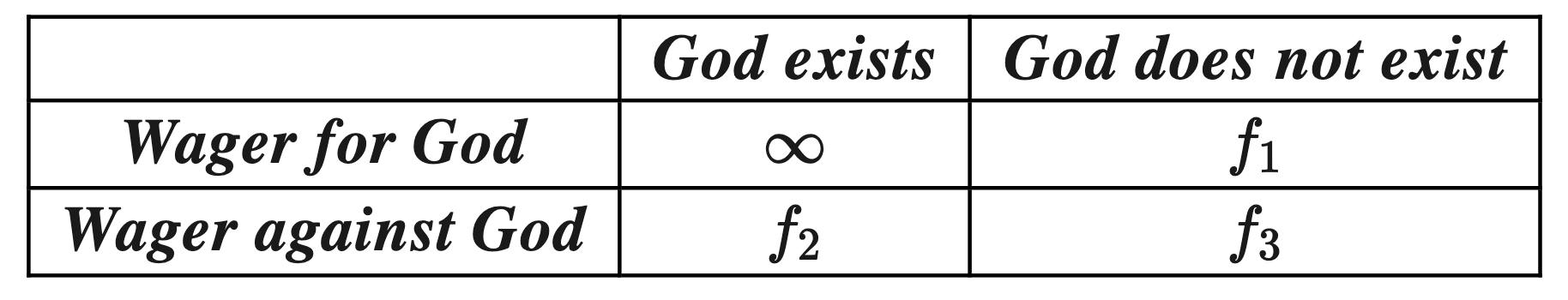

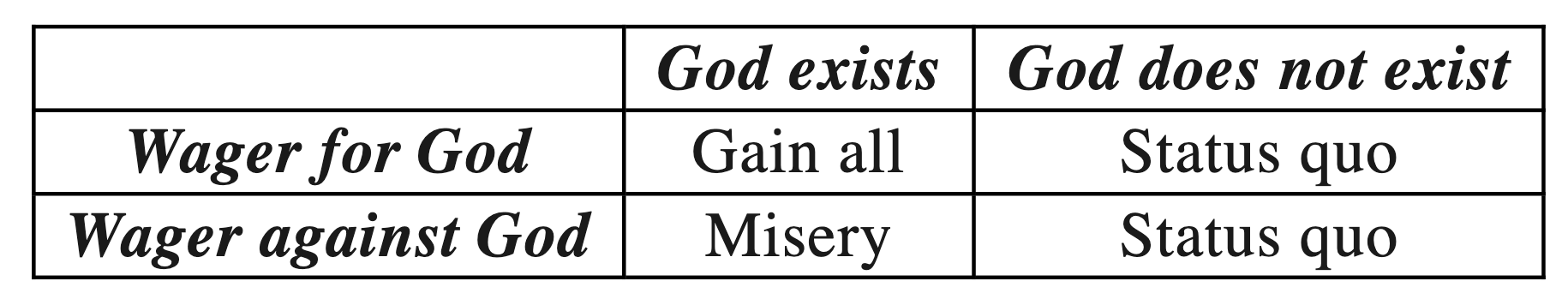

The online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provides the following charts which sum up what happens to those who believe and to those who don’t. Believers get Infinity and gain all, yet unbelievers get something far more limited, ranging from nothing and a finite something (f2 below) to Misery:

(Note: quotes from the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy are followed by “SEP.”)

I have no problem with the idea that belief gives you the expectation of infinity (God) and eternity (both God and the afterlife), although of course it may also give you (at least according to Pascal’s Catholicism), eternal torture as well. Yet leaving this aside, my main objection is that doubters and unbelievers can’t be left with nothing or some splintered or watered-down version of reality. They still live in the same amazing cosmos and in the same amazing body that believers live in. They still breathe the same air, imagine the same art, and have the same joys and sorrows.

In general, the wager tends to close down interest in the secular, physical world. This becomes even more clear when we remember that Pascal believes that the universe is an infinite abyss, and that the only thing that can save us from this abyss is God’s infinity, which fills everything with light:

… this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself (“ce gouffre infini ne peut être rempli que par un objet infini et immuable, c’est-à-dire que par Dieu même” — from the fragment Souverain Bien 2; trans. RYC).

This may be true, yet the wager makes our connection to this infinity and immutability dependent on our choice, as if we could possibly know how much of God’s light everyone will get. I doubt that any of us know for sure 1. how Grace works, or 2. what the real outcomes of our convictions will be.

The outcomes of the wager also suggest that this world lacks deep wonder, beauty, or worth in itself. Without remembering that it’s God’s Creation, it remains an infinite abyss. This wonderful o’erhanging firmament becomes a quintessence of dust. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that this physical world has no quintessence at all, no ether stretching into an infinity to be marvelled at; only a dust that obscures our celestial vision and leads us to the brink of the abyss.

When offered the choice between a heavenly sky fretted with the believer’s celestial fire and the unbeliever’s promontory of foul vapours leading into a meaningless void, who wouldn’t choose the fretting guitars of the angelic choir? But is this a fair way to frame our options? Or is it a subtle way of forcing us into a false dichotomy?

This isn’t to say that Pascal is wrong when he suggests that belief is a wonderful thing. I agree with him that belief opens up a vista of benevolent metaphysical possibilities. Yet 1. this vista can be in addition to, rather than instead of, physical possibilities, and 2. there are many vistas, and not all of them require confessions of faith or exclusive access.

Why not let the coin spin and watch the merry dance? Or why not take it to the store and buy something? In the store the shop owner will surely check to see that the coin has two sides before exchanging something of value for it. But Pascal would stop the spin and tell us that only one side counts. Nor does it help when he adds the threat that if there is a God and you don’t confess belief in this God you will not win everything. This ignores the possibility that God may have other plans, other timelines, other motives. God’s coin may have a beaming face on both sides — that is, He may be planning a universal salvation as imagined by Origen 1800 years ago, or by Richard Rohr last year. Or God may set the coin spinning for eternity. Or He may wonder what we’ll buy with our coin. Or He may want us to play some other game instead. Or, as Einstein suggests, He may not be interested in playing dice or any other game of chance. Who knows, He may not even be interested in speculative theology, that is, in defining or guessing at the cosmic rules that He clearly hasn’t made clear to everyone. Perhaps he really does operate like the Dao, which benefits the myriad creatures yet requires neither human belief nor gratitude. Perhaps a bird’s song or a loving sacrifice is worth more than all the high-sounding words in the world.

✝︎

Pascal’s bet divides human existence between Meaning & Infinity on one hand and lack of meaning & the infinite void on the other. Winning everything is the result of belief and not winning everything is the result of disbelief. Yet I’d argue that refusing Pascal's wager isn't to reject a meaningful Infinity. Rather, it's to reject the argument that a specific religious belief is the only way to reach a meaningful understanding of infinity. Refusing the wager is to reject the notion that unless we confess belief we're left with the opposite of everything: nothing. It’s also to reject the concept of a God who forces such a choice on us. A God who will smite us or nullify our existence if we use our free will to follow all possible truths. A God who commands us, Believe this, and only this, or else! In this sense, to reject Pascal’s wager isn’t to reject God, but rather to reject a version of God that’s doctrinal & exclusive instead of mystical & inclusive. From the point of view of the double refuge, the religious philosophy that makes most sense is is the one that says it isn’t the only one.

Pascal's wager might help people to escape from an entrenched positivism that refuses to explore emotional, romantic, transcendental, and mystical possibilities. But it doesn’t really help people who believe in the double refuge, that is, in a free flow from doubt to an open definition of God and spirituality. Unfortunately, given the traditional Christian view of the saved & the damned, the wager can also be used as a way of downgrading philosophical inquiry and existential exploration, to bring back instead the old notion that all human understanding is vanity. While the writer of Ecclesiastes makes a powerful point about the greater universe and the insignificance of humanity, it remains defeatist and depressing to apply such a vision to the things we strive for: meaning, freedom, charity, knowledge, progress, connection, compassion, etc.

What’s the point of using religion to make our ideals seem meaningless when they are the best things we can hope for — and when they in no way negate spirituality? At times, it may be that "in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow," yet one might add that it isn't the world, or our efforts in the world, that are in vain. Rather, it’s the opposite: any philosophy is counter-productive if it preempts or disdains our efforts to attain wisdom to make the world a better place. This seems an unavoidable conclusion, given that Ecclesiastes is praised as wisdom literature. Perhaps it’s best to say that wisdom literature is paradoxical at times, rather than it’s a vain waste of time to read about wisdom, as, say, in Ecclesiastes…

✝︎

Context

One must remember that Pascal’s Pensées is a diverse and at times fragmentary collection of ideas. Published posthumously in 1669, it can be read as either an internal or an external dialogue. As a result, it’s not fair to treat it as a philosophical treatise. Yet his wager is nevertheless an important argument, both in theology and in agnosticism. Many see it (or a variant of it) as a cogent and coherent argument against doubt and disbelief. Many also use it consciously or unconsciously, either as a fallback position or as a bypass at the crossroads of theology and logic.

Before going into more detail about Pascal’s wager, I’d like to acknowledge that Pascal is a brilliant mathematician and thinker who straddles the line between Medieval certainty and Modern uncertainty. Few essayists get at the precariousness of our human condition with such poetic concision:

All that we see in the world is only an imperceptible line in the ample breast of Nature. No idea can get at the size of these spaces.

Tout ce que nous voyons du monde n’est qu’un trait imperceptible dans l’ample sein de la nature. Nulle idée n’approche de l’étendue de ses espaces. (Pensées 22: Connaissance générale de l’homme. From the Port-Royal edition; all translations by RYC)

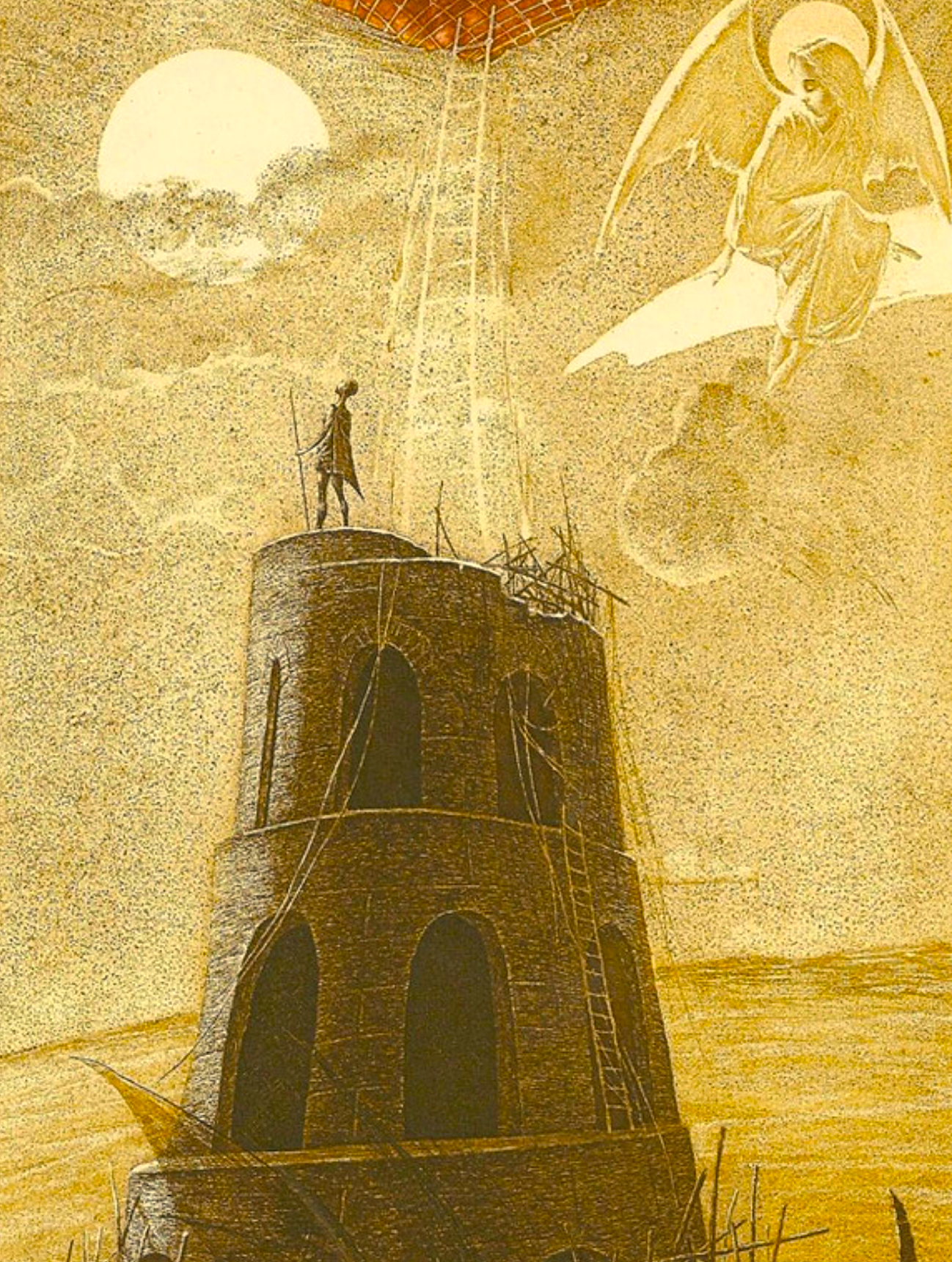

This is our true state. This is what narrows our knowledge into certain limits that we can’t get past; we’re unable to know everything and unable to know nothing at all. We exist on a vast middle ground, always uncertain and floating between ignorance and knowledge. And if we think to go further, the object of our aim wobbles, and escapes our grasp; it evades us, and flees in eternal flight: nothing can stop it. This is our natural condition, and yet it’s most contrary to our inclination. We burn with the desire to find depth in everything and to build a tower reaching to the infinite. But the whole building cracks and the earth opens up to the abyss.

Voilà notre état véritable. C’est ce qui resserre nos connaissances en de certaines bornes que nous ne passons pas; incapables de savoir tout, et d'ignorer tout absolument. Nous sommes sur un milieu vaste, toujours incertains et flottants entre l’ignorance et la connaissance; et si nous pensons aller plus avant, notre objet branle, et échappe nos prises; il se dérobe, et fuit d’une fuite éternelle: rien ne le peut arrêter. C’est notre condition naturelle et, toutefois, la plus contraire à notre inclination. Nous brûlons du désir d'approfondir tout et d'édifier une tour qui s’élève jusqu’à l'infini. Mais tout notre édifice craque, et la terre s’ouvre jusqu’aux abîmes.

Pascal is a poet of the vast obscurities, able to combine religion and skepticism in a way that inspires many people who want to make the leap from a Godless existential perception to an essentialist vision. He sees the type of alienation Sartre writes about three centuries later, yet finds in God an antidote: He vanquishes the deep abyss of ignorance and chaos with the infinite effulgence of His truth and order: “this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself.”

It’s as if Pascal foresees Sartre’s chestnut-tree root (from the section, “mercredi, six heures du soir,” in Nausea, 1938) and puts this existential symbol of alienation and absurdity into the epic story of Christian redemption. In Pascal, Sartre’s unnerving black symbol is instead a root that supports and nourishes the Tree of Knowledge, which makes all humans fall into the Abyss of Error, which allows them to rise, through Jesus, to the Heavens. Or, his God’s goodness blasts the evil root from the ground and we find ourselves walking in a garden somewhere in the sky, where no snaky root or underground horror unsettles the ground beneath our feet. Either way, Pascal’s God deracinates the problem of alienation and of all those other disturbing words that start with A: absurdity, anomy, angst, and above all atheism.

Yet one word that starts with A, agnosticism, remains largely outside Pascal’s ken. Rarely does he confront the full measure of agnostic doubt. When he starts to confront it, he ends up side-stepping it or conflating it with disbelief or chaos. This is understandable, given Pascal’s moment in history, when the discoveries of evolution, neurology, and genetics were centuries away. Nor were the philosophers of Seventeenth Century France in a position to assimilate the radically different concepts of God presented in Hinduism, Buddhism, or Daoism.

In Pascal’s France, the religious choice was to believe in the Western concept of God or not to believe in it.

Saka (2018, 190–191) [writes] that “Pascal's peers knew of Greco-Roman paganism, Judaism, Islam, new-world paganism, and multiple brands of Protestantism; they knew of alleged Satanism … and they knew, from their acquaintance with the foregoing, that still other religions could readily be hypothesized.” But still there is the issue of what probabilities should be assigned to alternative deities. (SEP)

Few people contemplated a return to the old pagan belief systems. Neoplatonism was still a powerful idea, yet Augustine had already integrated Plato into early Christianity, and Aquinas had already integrated Aristotle into Medieval Christianity. The complexity of Hinduism and the subtlety of Daoism were more or less unknown. For instance, the main Sanskrit texts were translated only in the 18th and 19th centuries. This is key to the historical context — and limits — of his wager, since in it God operates in the tradition of a jealous and anthropomorphic God who gives Grace only to believers. Such a strict religious system is alien to the questioning in the Vedas, to the many paths in Yoga, and to the doubts and speculations of Daoism.

Also, in Pascal's Seventeenth Century, science and medicine were in their early stages. While the scientific method was clearly understood, and while Pascal was a mathematical genius, scientific doubt was yet to yield the type of convincing explanation for human existence later furnished by evolution, neurology, and genetics. In astronomy, Pascal could be aware of Galileo’s Dialogue, published in Italian in 1632, and in French in 1634, yet he couldn’t be aware of Newton’s Principia, which was published in 1687. This was 25 years after his death. Science opened a huge area for doubt, and of course for Huxley’s agnosticism, which was of course both critical and open to religion.

I’d add to this timeline that Pascal also couldn’t be aware of the type of Romantic and Transcendentalist sensibility we find in Shelley, Byron, and Whitman. These poets accepted reason and empiricism, yet also left the path open to spirituality and metaphysics. For them, as for T.S. Eliot a century later, reason alone couldn’t grasp God, yet a unified sensibility, where reason and emotion unite, kept alive the possibility of a meaningful Infinity.

Pascal’s wager is based not on a range of religious, scientific, or agnostic options, but on a far simpler choice between belief in the Christian God and belief in a world with no other convincing theologies or deep avenues to truth.

✝︎

Pascal is extremely interesting to agnostics because he offers an in-depth understanding of why and how one might go from reason to faith. In this he prefigures Christian existentialists who leap from the material to the spiritual. My point here is that there are many ways to do this, and there are some ways that allow us to accept both sides — both the reason which understands the need for spirit, and the spirit which accepts the facts and logic of reason.

The reason I refer to the double refuge is that reason and faith are discreet, however much they might connect, and yet in the double refuge they are as close as two things can possibly be. The leap of faith suggests a landing on the side of faith, and the label of agnostic refers to a landing on the side of doubt. Agnostics understand why people take this leap, but they see it as an experiment. If they take this leap and like their new position as believers they would no longer call themselves agnostics or existentialists. They would see themselves as existentialists before the leap and essentialists after the leap. Existentialism and essentialism aren’t easily conflated or hyphenated. They may merge momentarily yet they finally remain separate, unless one can imagine a state of being in which one doubts and believes at the same time, which may be a type of schizophrenia or may be some super-state of consciousness yet to be understood. Yet for the moment, doubt and faith remain different things.

My notion of the double refuge is that this duality can be bridged this way and that, however often one wants, yet it isn’t a fusion. We might see it is a continual pivot, perhaps in the style of Zhuangzi’s pivot of the Dao, which allows us to look at opposites from a central point, one moment seeing the infinite divisibility of things and the next a unity that lies at the heart of this infinite divisibility.

✝︎

Next: ✝︎ Pascal 2: Six Problems