Le Bijou 1

The Star of Montmartre

☆

Martine loved acting, even if what she was acting was also real. On stage, she could be Beatrice one week and Medea the next. She could act out her hundred selves and still be one thing: the actress. And she was very good at it. The President himself had fallen for her latest triumph. Her mother, who had been a bit-part actress in her day, read all about it in the society pages. She routinely burned the reviews and accused the critics of ageism, of punishing la belle France with the flower of youth, which would only disappoint them in time. But Martine couldn’t care less. She told the President that all she cared about was the art of dissembling, and then gave him a wink.

☆

It was 9 AM and Martine was waiting impatiently for Kenneth at L’Etoile de Montmartre. She was waiting as an actress waits behind a curtain that’s about to rise.

Martine got to the cafe early in order to get the table by the front window, the one in the spotlight of the sun. She didn’t want him to miss a thing. She thought, I’ll meet him and give him the ring. He’ll have to wear it, or it’s over. And when he wears it, it’ll remind him of the story that goes with it. He thinks he knows everything. Kenneth was a visiting professor at the Collège de France, and it had really got to his head. Last week at the flea market he told her that she couldn’t tell the difference between an original Isis and a knock-off of the Virgin Mary. He seemed serious, but then he said he was joking. But she couldn’t tell the difference.

As usual, Kenneth was on time. She knew he would arrive on the dot — as English people loved to say, she thought sarcastically, as a replacement for spontaneity. So she had his favourite, a café crème, on the table thirty seconds before he sat down. Between her espresso and his café crème lay a sparkling ring, blue and silver. He started to say “Salu—” but she looked at him sharply, as if he were late for the show. The curtain was already half way up the stage.

She put her fingers to her lips and pressed them until the blood flowed away — from ruby to crimson, from scarlet to coral. It was as if she was mastering her emotions and could speak again. She pitched her voice an octave higher than usual, and inserted jagged breaks, to make her emotions seem even more real than they were.

She started abruptly, yet obliquely, like when the heroine blurts out the most significant details before the eyes of the audience have adjusted to the light: “There’s no way I could’ve known. I was having a drink with Antoine in the Latin Quarter. At La Maison de Verlaine, fifty blocks away. I had just bought this ring, this beautiful light blue ring. It’s exactly the same colour as the pendent my father bought me for my sweet sixteenth.” She pronounced the last two words with a Southern belle accent, which Kenneth thought was a wonderful thing to hear at any time (he could almost hear the echo of Tennessee Williams). It was especially wonderful coming from the lips of a stylish Parisienne.

She pointed between her considerable breasts and said, “This one.” But the pendant, on the end of its silver chain, was lost down there somewhere. She opened her blouse further so that he could take a better look. It was a foamy, light blue rock onto which Aphrodite herself might have emerged from a smooth white swell.

Something in its crystal lattice spoke to her. Would it speak to him too? She looked deep into his eyes, as if to draw them upward to the eyes of the protagonist on the stage. After a pause, she said, “I want to give you this ring. It will connect us. It matches your eyes. The dealer said it’s kyanite.”

She stared at the ring for several moments before continuing. “Antoine was telling me something about a course he was teaching. Japanese Anime and the Art of the Postmodern Something or Other. I was just pretending to listen. All of a sudden I looked at the ring, which seemed for just a fraction of a second to become darker blue and brighter white, both at the same time. I said to myself: My mother is dead.”

“At first I felt a heaviness, as if she were pressing down on my chest, like when I was in my teens. But then I realized I wasn’t responsible for what she did to herself. Why should I always feel guilty?”

Martine looked introspective, then hurt, then defiant, then continued: “I was sitting there, drinking with Antoine the whole time. We’d been there for three hours and were at the end of our second bottle of wine. He was saying something or other about manga — or manganese, or anomie, or anime, qu’importe! — while my mother was draping herself for the last time over her velvet chaise-longue, long past plastered, in her velvet and crimson living-room across from the theatre.”

Martine’s pronunciation was perfect, her intonation nostalgic yet precise. She was facing the existential drift of our tiny planet, and added: “Her eyes were fixed open, looking at the theatre across the street. Le Funambule, The Tight-rope Walker. From one stage to the next.”

“I can imagine the drama in my mother’s head in those last minutes, after she’d taken the poison. She would play her final role as Gertrude, her favourite character from Hamlet. She had rehearsed this role for years. She was always being poisoned by her husband, who hoped to poison Hamlet instead. She said that Claudius was too cowardly to stop her from drinking the poisoned wine. Every week or two, after three or four glasses, she would shout out, Le Cochon! He lets me drink it because he doesn’t want anyone to know that he’s to blame!”

“My mother blamed him for everything. Her death would prove it. But she also knew in her heart of hearts that he loved her, despite his evil ways. She whispered, Hamlet, the drink... and her head fell into a world of velvet.”

Martine looked up toward the window, as if she might catch the meaning of Fate as it passed by. “My mother died as the ghost died, as Ophelia died, and as Gertrude died: betrayed by them all. She drifted upward to the stars, joining Ophelia among the crowflowers and the long purples of heaven. And at the same time she drifted downward, into the river, a creature native and indued unto that element.”

Martine turned her gaze from the window to the table, and stared into the tiny black well of her espresso. Death was only a moment in time. And all too soon even the thought of the great void — le grand abîme — would also be gone.

She looked up at Kenneth. It was time for the protagonist to end the soliloquy, and bring the audience back to the real world. The coffee was the transition, the objective correlative. She cast her eyes slowly along the table, passing over the blue ring, to his café crême. “That’s how I think of it now. Back then, all I knew was that she was dead. The blue ring told me. I solemnly raised my glass to Antoine, and said to him, My mother is dead.”

☆

Martine had told Ken the story of her strange intuition a number of times. Each time, it bothered him to think of a mind that could experience such a thing. A mind he was otherwise enchanted by. But what bothered him this time was that her experience occurred while she was drinking with Antoine. That part of the story was new.

Ken was never quite sure what Antoine meant to Martine. She often stopped herself short when she started to talk about him. Antoine kept calling her on his stupid pink cellphone with the Hello Kitty beep, which he called ironique. Ken wondered if there wasn’t something less than ironic about his irony. Martine said they were just friends, but Ken couldn’t get used to the way they kissed each other hello and goodbye, as if it were part of some great drama. He’d pull her toward him with one hand, his fingers creeping up her back and disappearing somewhere near the clasp of her bra. Then he’d pull her face closer to his lips, adding a mock gesture as if to say, Oh, darling, the servants have put out the candles on the veranda!

Martine loved that sort of thing. Ken didn’t know if it was because she was French or because she yearned to be back on the stage. Yet whenever she dipped into Antoine’s arms, she didn’t look into Antoine’s eyes, but into his.

☆

Martine was in tears now, the way she used to do it as a teenager at Le Funambule. She had it all balanced internally, as if she were a tightrope walker. On one side she was thinking sadly about her mother on the crimson velvet. On the other side she was remembering the time when she was fifteen and her father told her that she was the most beautiful girl in the world.

She was heading out the door, confused about who she was and how she’d make it through the school year. No one understood her, and she could never say what she really felt. She felt like an alien. She saw the root of Sartre’s chestnut tree, from his novel Nausea, which she had to study for exams. The root was dark and sinister, creeping out from the earth, making her feel slightly nauseous. Her nerves were shot and she had two small pimples above her left eyebrow. That morning she had a twenty-minute oral on Meaning in French Literature. Only the French could do this to their children. Her clothing was too tight in one place and too loose in another when her father stopped her and told her that she was the most beautiful girl in the world. He kissed her on the nose, and watched her lift up from the floorboards and fly out the door.

Three years later her mother had worn her father to the ground. Martine often saw him on her way to university, under the elevated metro at Barbès, hawking kaftans and leather hats from Senegal. He had a thing for African women. He called them the farthest thing from les salopes de Montmartre. She remembered seeing him a week before he died, disappearing down Rue de la Goutte d’Or, bewitched by the swaying hips of an African woman half his age. Martine swore to herself that she would never be like her mother.

☆

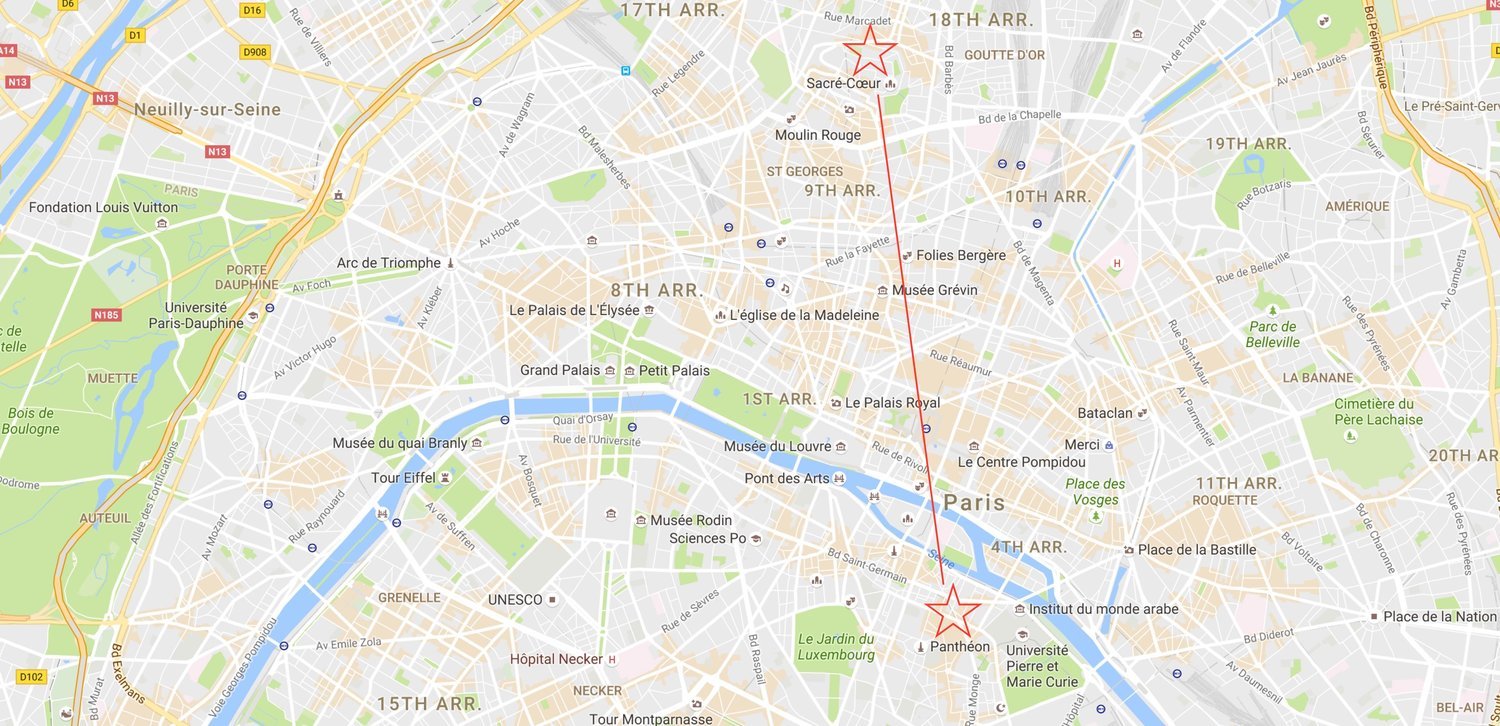

Whenever Martine thought of her father, tears welled up in her eyes, as they did now, proving to Ken that she couldn’t possibly be making it up. Intuition he could believe. But telepathy? How could that be part of the equation? Part of what equation? Martine had told Ken wildly different versions of the story. The scenarios shifted this way and that, but one thing didn’t change: Martine was convinced that she knew the exact moment her mother was dead. It doesn’t make sense, he told himself, yet there it was: a woman sitting in the 5th Arrondissement knew that her mother was dead in an apartment in the 18th.

Ken searched his mind to make sense of it all. Could Martine’s brain have somehow made a connection with her mother’s brain over that distance? Could some wave or particle, or some combination of waves and particles, have communicated across the Seine and over dozens of busy streets from one body to the next? Did it travel through some fifth essence, some as-of-yet undiscovered form of sub-molecular space? Or was this just another way of giving fantastic names — this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestic roof fretted with golden fire — to the quintessence of dust?

Or perhaps Martine’s intuition had something to do with DNA. Was it possible that strands could communicate with each other? If so, then wouldn’t they communicate most with strands that were most like them? From parent to daughter, they even emitted the same signal: I am the Monarch of Drama Queens.

But did he really believe this? Even if it was possible, was it probable? And didn’t probability trump possibility? Did Kenneth really believe that his neurons were being manipulated by some unseen subatomic force, or that his brain worked like a wireless transceiver?

And yet there it was: a light blue kyanite ring that spat in the face of Science.

☆

Next: Le Bijou 2: The Scholar