The Double Refuge 🦋 Butterflies Landing

On Nightingales & Unified Sensibility

Keats’ Nightingale - Unified Sensibility

🦋

Keats’ Nightingale

Even if we could somehow get at clear causes and effects for thoughts and feelings, cause-and-effect analysis doesn’t necessarily get at the nature of experience. For instance, we could find a neurological explanation for the brain’s sluggishness when it slips into the realm of imagination. This would be fascinating from a medical viewpoint, but it wouldn’t help us understand this experience experientially, nor would it get at this experience vicariously. If it’s experience we want to understand, it might be better to look at Keats’ poetic exploration in “Ode to a Nightingale”: “My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, / Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains / One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk.” A neurologist might explain in systematic terms Keats’ fantasy of death, with its liberating skies and its bird-notes in the depths of the forest. Such an explanation would be a fascinating contribution to science and psychology. By contrast — but not by replacement or subordination — literary exploration has a different value, one which gets at the feeling of the experience, at the re-created sense of it in words. And at its enduring mystery.

In Keats’ poem, the nightingale’s song transports the poet from thoughts of death to thoughts of nature and flight. This music is the same “that oft-times hath / Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam / Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.”

In his imagination, Keats travels far away from the grim thoughts of the earlier stanzas, where he thinks of hemlock and Lethe, and “Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies.” He floats with the beauty of the nightingale’s voice: he sees the “White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine; / Fast fading violets covered up in leaves.” He scents “The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine.” He hears “The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.”

Keats takes us into this world of fancy and fullness, yet toward the end of the poem he also takes us back to the real world: he realizes that even in the far-off world of the imagination, there are perilous seas and the possibility of being forlorn: “Forlorn! the very word is like a bell / To toll me back from thee to my sole self! / Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well / As she is famed to do, deceiving elf.”

Keats presents us with a journey away from reality and back to reality, all the time keeping true to the propensity of the mind to wander, to probe, to imagine possible scenarios, and yet also to accept the physical 4-D realities of our existence. His poetry has a sort of phenomenological rationale which isn’t averse to rational explanation, but which doesn’t need to be explained in rational terms. In this sense, his poetry illustrates the double refugee mode of operating, according to which we explore life with creativity and gusto, yet we return again and again to the facts of our human experience in the real world. However high our heads are in the clouds, where we may see a flock of angels or a flotilla of aliens, we remember that our feet remain on the revolving surface of Earth.

🦋

Unified Sensibility

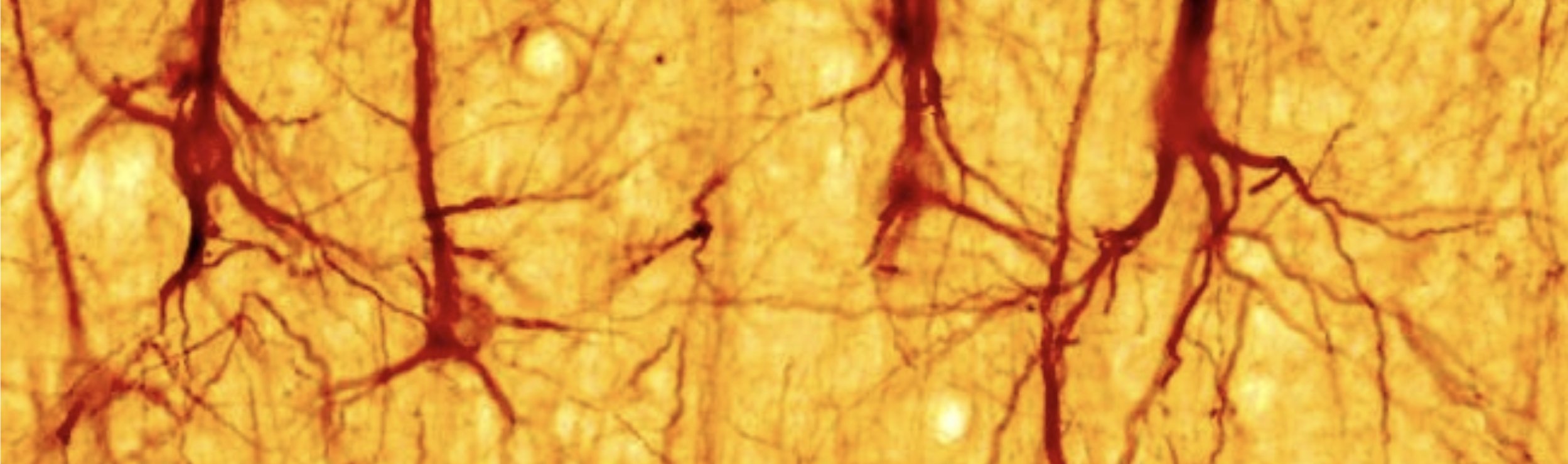

In thinking about the nature of our existence, I assume what poets like Keats also assume: that there isn’t necessarily a divide between thinking and feeling. We see this in the ancient Indian concept of Yoga (from the Sanskrit yoke or union) and in the most recent science: each year neurologists see more deeply into the way sense neurons connect to the massively complex neuron structures of the brain.

Thinking and feeling aren’t two sides of the same coin as much as they’re two intermingled metals, like the copper and zinc in brass. In thinking about brass, some might put stress on the copper and others on the zinc, yet brass contains both elements in an integrated structure. In terms of belief systems, some people stress thinking or rational explanations while others stress feeling or spiritual explanations. For double refugees this divide between thinking and feeling is a false dichotomy. They wonder if our time might be better spent integrating the two.

In his 1921 essay “The Metaphysical Poets,” T.S. Eliot argues for the unification of thinking and feeling. Focusing on 17th century poets such as Donne and Marvell, Eliot champions “direct sensuous apprehension of thought, or a recreation of thought into feeling,” as well as “transmuting ideas into sensations, of transforming an observation into a state of mind.” He suggests a historical context for our present dissociation of sensibility, one which fits with the shift from Renaissance man to Enlightenment intellectual: “In the seventeenth century a dissociation of sensibility set in, from which we have never recovered.” Yet he also suggests that the Romantic poets Shelley and Keats display something of the earlier unified sensibility:

In one or two passages of Shelley's Triumph of Life, in the second Hyperion [by Keats], there are traces of a struggle toward unification of sensibility. But Keats and Shelley died, and Tennyson and Browning ruminated.

Eliot stresses that unified sensibility requires an integration of heart with mind, including the physical elements of the brain, that paramount organ which is deeply, deeply integrated with the body:

Those who object to the 'artificiality' of Milton or Dryden sometimes tell us to 'look into our hearts and write'. But that is not looking deep enough; Racine or Donne looked into a good deal more than the heart. One must look into the cerebral cortex, the nervous system, and the digestive tracts.

The nervous, circulatory, digestive, skeletal, muscular, and exocrine systems are all parts of one human system, and separating any one of them would mean death. Likewise, to divide the intellect from the senses and emotion would mean the death of meaningful human thought.

Coming back to my notion that the self can be seen in terms of brass (a mix of copper and zinc), one might also experiment with another element — tin, silicon, or manganese — and see what happens. Perhaps this third element might be able to stretch the heart and mind, so that it takes on the quality of the spiritual or platonic love that Donne writes about in “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” (1611-12):

Dull sublunary lovers' love / (Whose soul is sense) cannot admit / Absence, because it doth remove / Those things which elemented it.

But we by a love so much refined, / That our selves know not what it is, / Inter-assured of the mind, / Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss.

Our two souls therefore, which are one, / Though I must go, endure not yet / A breach, but an expansion, / Like gold to airy thinness beat.

In a poetic or double refugee sense, this third element is spiritual manganese, magical silicon, or etherial tin. It expands the metal of our selves so that its filaments reach out into the atmosphere, even to the heavens, “like gold to airy thinness beat.”

Such a state of unified being may or may not be spiritual, as Donne claims it to be. It may or may not be caused by an unknown spiritual essence, which can be seen as a a fifth essence (a quintessence) or as the third element I made up: etherial tin. If this mysterious element (or essence) is indeed heavenly soul, then it isn’t at all clear how it jives with the paradigm of scientific proof required by atheists and positivists. A double refugee would note that 1. we don’t necessarily need proof that it exists if we experience it, and 2. we may simply lack metres sensitive enough to detect it, just as we couldn’t detect bosons or distant galaxies prior to the 20th century.

A determined theist, Donne underscores the old Gnostic distinction between matter and spirit, even while hinting at the possibility of interpenetration in his gold metaphor. While Donne is condescending on this point, he makes it powerfully: a dull sublunary lover (that is, a lover of limited earthbound perspective) whose soul is sense (whose psyche sees everything in terms of physical reality) cannot, by reason of his own rational parameters, admit (entertain) the notion of a spiritually-charged emptiness. Such a dull sublunary lover restricts his vision to the world of physical things, to a world of causes and effects. In such a world, nothing comes from nothing.

Donne is comforting his wife because he’s about to go on a journey, yet what he says can be applied to platonic love and spiritual experience in general. Their love is so much refined that it transcends understanding: their selves know not what it is. Perhaps this is why Donne uses extended metaphor, rather than pure reason, since this metaphor helps him get beyond the impossibility of explanation (Dante’s Paradiso is dedicated to this poetic tack into ineffability). And yet Donne likens the abstract experience to something one can grasp: the extension of a metal. The metaphor isn’t some vague well-worn phrase like my heart is an ocean, but rather a specific physical thing: gold. This element is undeniably real, undeniably solid, and undeniably capable of being stretched to a point that is seemingly miraculous.

Essentialists and theists believe that out of apparent nothingness, out of thin air, comes spirit. Or, to put it in terms of theistic chronology, spirit has always resided in nothingness, just as God resided in the formless waters of the original void. While atheists and positivists cannot admit / Absence, because it doth remove / Those things which elemented it, theists and essentialists do admit spiritual absence. They feel it and think it. Were they to call it presence they would be forced to double back and admit that there’s no way to show or prove the existence of this presence here in the physical world. Absence, capitalized or not, does a better job of describing something that is in the air, but is so thin that it cannot be apprehended by the senses. Hence, the lovers Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss, that is, they don’t worry about the absence of physical closeness or the ability to touch each other since they’re connected on a higher, or lunary, level. They don’t deny the body, but suggest that the love within their bodies can unite them even at a distance, in the finest, thinnest form possible, like gold to airy thinness beat.

🦋

The open agnostic hovers over the poetry of Donne, then dips his feet into the honeyed current. He wonders if it might be true. Is there a beating heart in the airy thinness of heaven? Is there a meaning beyond these bodies of ours?

The open theist dives.

With golden shoes the refugees dip downward and drift upward, pulled away by a cinnamon girl current of air, or a milky slipstream of stars.