Nothing in Damascus

The Outcast - The Pentagon - Infinity & Nothing - The Golden Star - Scrolls - Lines on Rosewood - The Line - The Necklace - Lamp-Black Eyes

⏦

The Outcast

The Bakhshali manuscript is an ancient Pakistani mathematical text written on birch bark [… It] contains the earliest known Indian use of a zero symbol. — Wikipedia

~ 808 A.D. ~

Once upon a time in Damascus, during the reign of Harun al-Rashid, Zaphnathpaaneah the rabbi walked through the bazaar with his head held high. He held it high above the multitude that swarmed with delusions and lambs on a spit — until Augustinius bumped into him near the melon vendor. Their noses vied for who could sniff the highest air. Who had the right to be called The Chosen People.

“We were here first!” cried the rabbi.

“We completed the prophecy!” cried the priest.

Behind his fruit-stand counter, Muhaymin the desert tribesman got up from his bench and pulled the tarp from one side of the street to the other. Sitting back down, he commented to his friends, “Haven’t they heard that Allah gives shade to us all? We are all People of the Book — except the worthless idolators, of course. There’s only one God, but not for those who think there are a ten thousand.”

Yet already there were three versions of God, according to the count made by Bakhshali, who everyone called the Outcast from Hindustan. Bakhshali had heard the tribesman’s comments, since the fruit-stand was within spitting distance of the gem-shop veranda where he was sitting.

Bakhshali had been kicked out of the temples and churches because he argued that all versions of God cancel each other out — and because he was an Untouchable, the lowest of the low, the scum of the Earth.

Or, at least his family in Gandhara was Untouchable, until his parents converted to Islam when Bakhshali was 17 years old. Yet by that age Bakhshali had already been seduced by the great god Shiva and by the notion that gods are just stepping stones to a greater Reality beyond everything. But his personal journey didn’t interest the Hindu pandit, who told him that no one comes to God but through Krishna. And it certainly didn’t interest the local mullah, who told him that if he didn’t forget where he came from he would live to regret it.

Rabbi, priest, pandit, and mullah all joined forces, making sure that the inconvenient scoundrel landed face-first in the mud. No one but Babak the Persian gem-dealer wanted to hear talk about equality and religion from an apostate who had nothing to sell.

⏦

Having been cast from the temples of fragrant incense —

away from the bishops in their bright red gowns,

from rolling Vedic chants and geometric renown —

Bakhshali could be found sitting with Babak,

who was always yawning (Bakhshali’s scrolls kept him up all night)

under the awning of Babak’s gem shop, scribbling on his scrolls.

Occasionally Bakhshali looked up, as if he was waiting for some miracle to occur. Some magic that his quill might etch in the market air.

⏦

The Pentagon

In the heat of the afternoon there were no customers. Bakhshali and his friend the Zoroastrian gem-dealer had been sitting on the long rosewood plank for hours. They sat with their backs to the store and their eyes to the world outside.

Babak had travelled this world — from Damascus to Dublin, from Baghdad to Borobudur — yet he’d never met anyone as strange as his Hindustani friend Bakhshali, with his mania for geometry, mathematics, philosophy, religion, and politics.

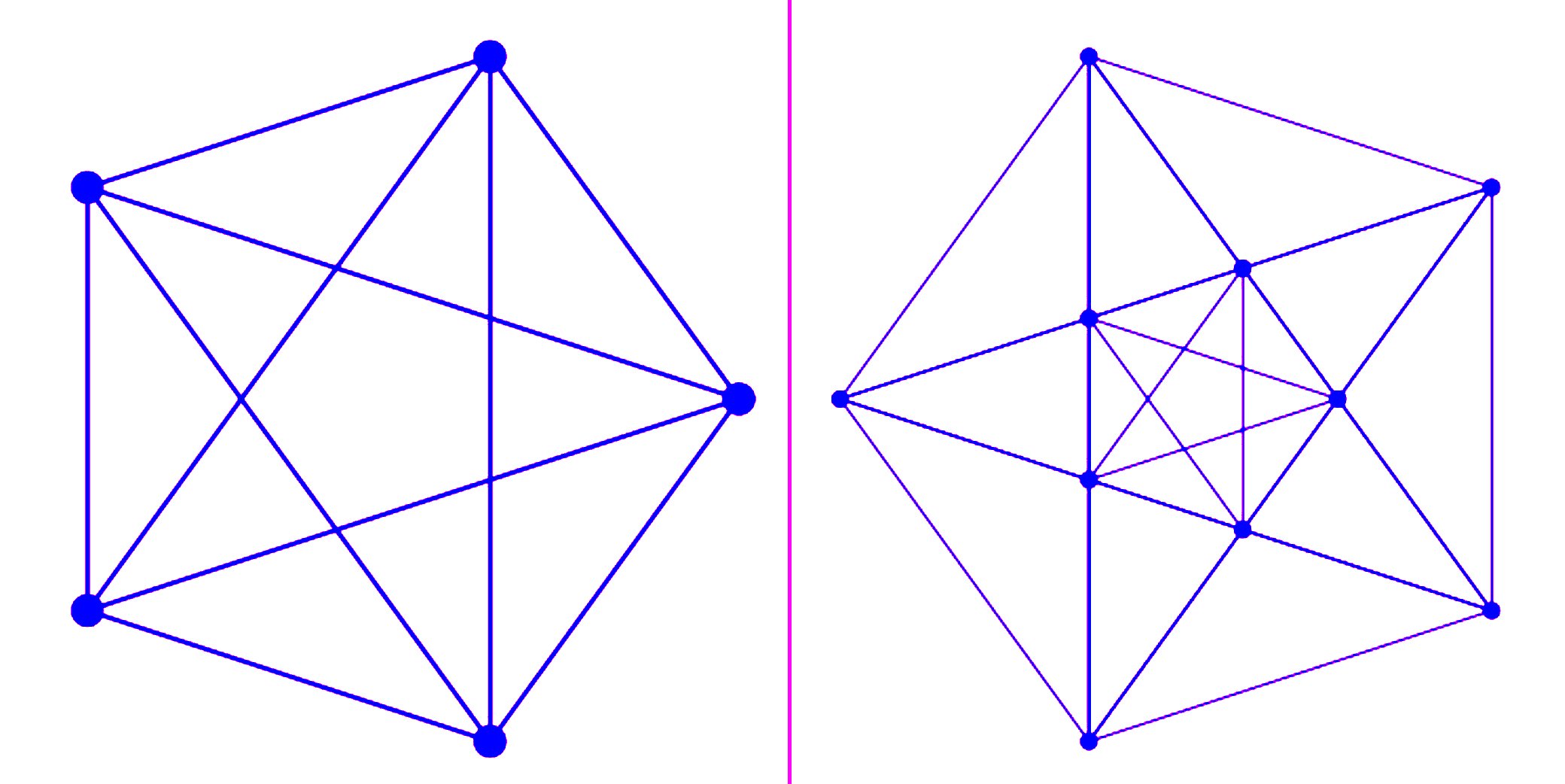

Several weeks ago, they had a wonderful discussion about these fields of study. Bakhshali called them the five-pointed star. He then drew five blue dots on a scroll. He wrote, in his fine quillmanship, Geometry, Mathematics, Philosophy, Religion, and Politics beside each dot. Connecting the dots to make a pentagon, he asked Babak to imagine an institutional building in that shape, with no windows and with two sentries at the only door.

With his ruler, Bakhshali connected the dots internally, or, as he put it, “inside the building where everyone is blind.” Babak looked at him, not as if to say he didn’t understand him, but rather as if to say he didn’t understand him yet.

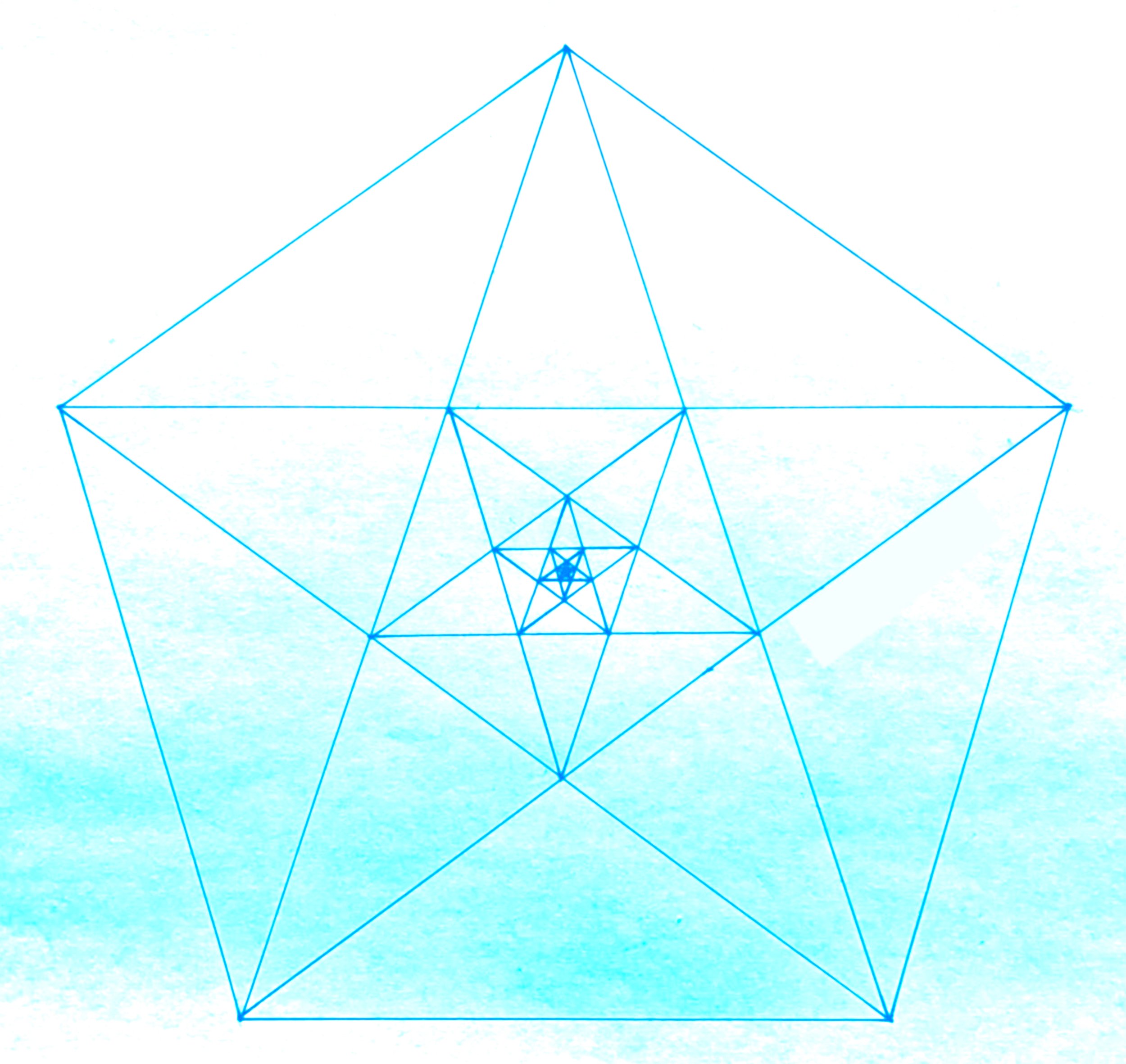

Bakhshali explained: “Well, they may not all be blind. But most of the councilmen and priests and judges seem to be seeing things. Spies instead of allies. Snakes where there’s only a rope. Sinners where there might be saints. They don’t know that the pentagon holds within it a star, which holds within it another pentagon, and another star, and another pentagon, ad infinitum, as the Romans used to say.”

“Eventually the pentagons and stars fall into their own centre, denser than we can see, but not so dense that math can’t make sense of it.”

“I call this the infinity principle, because it can go on forever. Mathematically, at least.”

Bakhshali had jumped quickly into abstraction, while Babak still wondered about the fate of the councilmen, the judges, and the priests, who were probably just trying to do their jobs. Bakhshali interrupted Babak’s thoughts, and asked, “What if they were suddenly gripped by a curiosity to see the other rooms of the building, to ask questions that were beyond their sphere of knowledge, perhaps even beyond answers? What if they walked into the centre of the pentagon, and fell into the oblivion of the imploding stars?”

Babak suspected that Bakhshali was hoping for this outcome, given he was still bitter at having been thrown out of all five religious buildings in the town. Synagogue, cathedral, mosque, temple, even the Zoroastrian Darb-e Mehr, the Door of Kindness, had been shut in his face. Augustinius the priest was particularly vehement. He made it his life’s mission to tell everyone that he would never let a faithless good-for-nothing like Bakhshali darken the steps of his Church. He encouraged all the other religious leaders to place a permanent ban on what he called “this piece of good-for nothing trash.”

The old men playing backgammon in the square muttered against Augustinius’ nonsense. One old man asked indignantly, “What will he try to ban next, entry to the Grand Mosque, our beloved al-Jamiʿ al-Umawi? Or to the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, our pride and joy, Bayt al-Hikmah? The old men were so incensed by Augustinius’ dogmatic babble that they refused to allow their wives to even talk about it.

⏦

Infinity & Nothing

In the cool shade of Babak’s veranda, Bakhshali worked his ruler ever more finely, arriving at a point where all the lines overlapped. All that his quill touched was a single blue dot. “At a certain point we can’t see the difference between the five points anymore. They’ve merge into one. And yet within the tiniest of pentagonal dots are thousands, millions, trillions of pentagons and stars, forever imploding as you count, until you give up counting, defeated by the pure mathematics of it all.”

“Math doesn’t just get you to imagine infinity, like the red-gowned priests or the saffron-clad yogis. Nor does it just talk about social unity, like the magistrates and councilmen. Rather, it demonstrates these things logically, spatially, right before your eyes.”

“You can use any shape, putting one inside the other. They’re called fractals, although the mullahs like the ones with stars and moons. The priests like the crosses, and the wandering saddhus will take anything. The five points of the star could represent Islam, or they could represent the five rivers of the Punjab. Or they could represent the five religions: Islam, Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Hinduism. Or they could represent five of the Hindu gods: Shiva the Destroyer, Shakti the divine energy, Ganesh of the perfect mind, Vishnu the preserver, and Surya the light of the sun.”

⏦

The Golden Star

Bakhshali cleaned his quill in the little jar of water Babak kept fresh on the table, next to his coffee cup. Picking up a second scroll, Bakhshali asked Babak if he could use some of his “special ink.” Without a second thought, the gem dealer went deep into his shop, opened a locked compartment, and brought back a golden jar. Bakhshali didn’t know how much it cost, and Babak didn’t care.

Using the golden ink, Bakhshali drew a carefully-studded design of stars on his scroll, which was jet black. Bakshali called the black scroll “a landscape of infinity.”

Bakhshali held the scroll into the light so that Babak might see it more clearly. “This golden star is just another case of infinity stamped into infinity. The essence of religion, like the essence of politics and art, is infinity. Each part — whether it’s geometrical, mathematical, philosophical, religious, or political — is connected through fractal infinities and through the interconnection of their design. As a result, all claims to superiority — all claims of a part being above the whole — always come to nothing.”

When Bakhshali went on like this about stars and stripes, sickles and equality, most people assumed he was insane. Yet Babak didn’t think so. Indeed, most evenings he carefully picked up the scrolls that Bakhshali had worked on during the day, yet left scattered on the table or on the veranda floor, before wandering off into the evening, in search of what he called the white jewel of the night. Babak had a whole armoire filled with his friend’s diagrams, graphs, and written paragraphs interspersed with arcane symbols, formulas, and equations. He called it the armoire of the gods. He spent half the night pondering what they meant. Bakhshali, on the other hand, spent half the night searching for a diamond in the sky.

⏦

Scrolls

Babak scratched his head at how his friend mixed incongruous things — numbers with letters, letters with strange symbols. He sometimes felt that he was wandering among the strange ruins of Uruk or Harappa. Yet at other times, after staring at the scrolls for three or four hours, when the moon struck the table in the silent middle of the night, Babak remembered what Bakhshali told him earlier in the day. “A number is just a way of referring to quantities of things, which are also indicated by letters. Letters and numbers on either side of the equation must, however, cancel each other out. They must reach a point of perfect equilibrium, as the stoics and the yogis say. Unless you believe that God lacks a sense of balance or proportion.”

At moments like these, the numbers and letters didn’t seem incongruous to Babak. Instead, he imagined a strange symmetry in the lines of numerals and script, as if some hidden power were trying to speak to him through Bakhshali’s incantations of lines, digits, and circles.

Whenever Babak felt this sliver of meaning, he’d show the scrolls to his friends the next morning. His friends were builders and carpenters, magistrates and professors, yet none of them understood the complexity of their design. After several minutes of trying to make sense of the gibberish they saw, they looked at Babak with condescending pity. They suggested, as delicately as they could, that there was a difference between mixing things and mixing things up. On their way home they’d say to each other that Babak was an honest man, but that the Zoroastrians had lost their way long ago.

⏦

Lines on Rosewood

Looking over at Bakhshali’s scroll, Babak saw that today his friend was obsessed by lines with dots on them. He asked, “So, what are you working on?”

Bakhshali jumped a bit inside his skin when he realized there was another human being sitting next to him. Yet the sight of two half-filled coffee cups beside him on the table was reassuring. People used to tell him to wake up and smell the coffee, but he had no idea how it smelled. Only when it hit his tongue could he appreciate the flavour.

On his white scroll he’d drawn a single line which went from one side of the scroll to the other. Babak could see that Bakhshali meant the line to go to the very edge of the scroll, for his quill had marked the table where it continued past the scroll. He even punctured the table with several blue dots, oblivious to the sheen and the green-tinted design of the Simurg, that mythic bird who flies beyond all dimensions to God. This carelessness seemed strange to Babak, since Bakhshali was usually such a careful draftsman.

The table was varnished rosewood, and would never recover. Yet Babak saw both little blue lines and each indented blue dot as a sign of something else. It was evidence of his friend’s inner world, imprinted on rosewood space and recorded in time over lazy Damascus afternoons. To Babak they seemed like blue stars and asteroids flying, like the Simurg, across the rose-scented heavens.

⏦

The Line

Bakhshali had drawn three symbols on the horizontal line, all close to the centre of the scroll. There was an empty circle on the left, a filled-in circle on the right, and a thin vertical line half-way between the two circles. The empty left circle was the same distance from the line as the full right circle.

Then, as usual, Bakhshali started talking as if he’d already said hello to his audience, introduced his theme, defined his terms, and explained his methodology. He’d of course done none of these things. But Babak was used to his abrupt beginnings. The working title for the armoire scrolls he hoped to publish one day was In Medias Res.

“Between the empty circle on the left and the full circle on the right there isn’t a void, but rather a marker, call it akasha or zero, it doesn't matter to me. The circles on either side of the vertical line could be anything, even concepts. For instance, you could put any god, or any number of gods, on either side. With any power. To any power. On the right is the positive field, the gods in all their finery, and on the left are all the things these gods aren’t, the debts or negative spaces the gods incur in their own absence.”

“Or think about the negative as the Indian gods the Persians turned to demons. Our good devas became their evil daevas. Or think of the demons we both turned to gods. We used to be one people once, coming down from the northern hills. And yet now our deities are polar opposites of each other. Just like the great god Baal became a demon in the Jewish story. Beelzebub, Lord of the Flies.”

“Or think of the line as a line of latitude, stretching from Asia to Europe, along the Silk Road and beyond. The line spills out over the table, to the east beyond the glory of Nishapur to the island of Java. To the west the line stretches beyond the Turks and the Normans, all the way to the wretched English, who even the Romans couldn’t civilize.”

"Or imagine that one people writes on one side of the scroll and another writes on the other side. They revisit their writings on occasion, erasing the earlier writing so that only faint traces remain. Each side of the scroll is a palimpsest, with the past receding deeper and deeper into the fainter etchings of meaning. Go deep enough and all past writing is lost, and the two sides are the same. In the depth of the paper there are no lines or curves, let alone bright circles of blue, empty or full. Only nothingness, an empty slate, deep in the heart of zero."

⏦

The Necklace

Bakhshali looked up at Babak, whose eyes were swirling, and asked, "Can you get me a gold chain? And two beads, of clear and black diamond?"

Babak was used to Bakhshali's odd requests, so he got up, selected his finest gold chain, as well as two of his finest diamond beads. He didn’t tell Bakhshali how precious the black carbonado diamond was, and how difficult it was to get it, from a line of traders that stretched deep into the heart of darkest Africa. He merely set the two diamonds on the rosewood table next to the scroll.

Bakhshali picked up the chain and made a knot in the middle, then strung the clear diamond to its left and the black diamond to its right. "Or think of the gods as gems. The black diamond on the left is the negation or absence of a god, and the white diamond on the right is the affirmation or presence of a god. Give the full god-gem on the right the quantity of plus 1 and the empty god-gem on the left the quantity of minus 1. Add whatever qualities and quantities you want to the gods on either side.”

“Then multiply plus 1 or minus 1 by the vertical line between them, which appears to be nothing, a mere in-between, but is in fact the specific thing called zero. The sum for +1 X 0 or -1 X 0 will be zero. The line in the middle is like the middle of a teeter-totter, evening out the weights on either side. The great equalizer. Last year I got into alot of trouble for saying Like Shiva the great destroyer of worlds and for saying each side cancels the other out. So now I just say they balance each other out.”

“I tried to explain to the priests that the Zero wasn't nothing. But I kept coming back to the idea that it was in fact Nothing with a capital N. Or Zero with a capital Z. I tried to get ecumenical about it, calling it the Holy Spirit, the name of God that can never be spoken, but I kept coming back to The Full Void.”

“You’d think that the Hindu pandit would have understood what I was talking about. But all he could talk about was Ram, and how Ram was Vishnu, and how Vishnu was Everything, not Nothing. The only person who understood what I was getting at was a traveller from China. We chatted about Nothing all afternoon.”

“The traveller told me that in the far eastern hills only the biggest idiots in the land dare to give it a name. Everyone else calls it the Way, attempting to be as vague as possible. They say it turns slowly in darkness and resembles the forefather of God. Or it’s God, but without attributes. Everything else we see around us, and everything we can conceive, are the attributes.

“So, take a god, any god, capital or no capital, or any number of gods, or any number of things for that matter, then multiply this number by the Central Point, the Thingless Thing called Zero, the Empty Air, Akasha, Spirit, Ether — whatever you want to call it. You could even just call it That, and imagine everything else that we can see or imagine in this world as this. Multiply whatever you can see or think of by That, and the sum remains That. All this is That.”

⏦

Lamp-Black Eyes

Bakhshali was quite proud of his reasoning, until he looked up and saw Ruxshin come around the corner. He dropped his fine Egyptian blue fountain pen onto the table, got up from his rosewood seat, and walked into the bazaar.

Bakhshali still had the necklace of rubies in his hand, but Babak said to himself, What has he taken? What has he given? We were one people once. In any case, the necklace ought to be hanging around Ruxshin's ivory neck. And when he clicks the lock at the back of her neck, the far-flung lines of his world will come together and he’ll know that on one side is Nothing and on the other is Beauty, all strung together along the golden circle of Infinity.

Babak looked at the scroll on the table, with its three little symbols hanging on to the line for dear life. He then looked at the scroll with the golden star on the black background. He went into his shop and brought out the darkest ink he had: lampblack, culled from the soot of oils that once lighted his fellow humans the way to dusty death. Dipping a quill in the inky night, he copied beneath the golden star a poem written several centuries ago by Bhartrhari: “The clear bright flame of man’s discernment dies / When a woman clouds it with her lamp-black eyes.” It was barely possible to make out the moist words of the poem on the black paper.

⏦

As he walked across the open space of the market toward Ruxshin, Bakhshali thought to himself, Let them litigate heaven and earth, there’s no law that can stop our inevitable union. So what if she’s white as a Persian queen, and I’m black as Harappan pitch? Our children will be the honey-colour of dawn and the amber beauty of dusk.

⏦

As the ink dried, the words became invisible. But Babak knew that the words were there. And he knew that Bakhshali would soon find his constellation in the Damascus night.

⏦

Next: 🇩🇿 🇫🇷 Transparently Multicultural