Le Bijou 2

The Scholar

☆

This time Kenneth was waiting for Martine in the Latin Quarter. She’d asked him to meet at La Maison de Verlaine, with its heavy echoes of decadence and symbolism. He hoped she wouldn’t be late, since he was scheduled to give a lecture in an hour at the Collège de France (just down the street), which had generously kept him on for another year. He was expected back at All Souls in September, with or without Martine.

Martine was the best thing, and the most confusing thing, that had happened to him in his two-year stint at the College. On the surface, she and the College were opposites: she was volatile and emotional; the College was solid and rational. And yet she was brilliant and creative, like so many of the professors he’d met, whose studies in everything from bosons to cuneiform boggled his mind. The deeper he got into her thinking, or into the thoughts of his colleagues, the more confusing things got. Everything started off in a straight line, as in polite conversation. Comment vas-tu? Très bien, merci. Yet everything ended up in circles, wide loops, or tight knots. Mais, je croyais que vous étiez… But, I thought you were…

Like a glass menagerie, the neat structures splintered under the pressure. It started with a clear line of poetry, like a unicorn of rare device, and ended up with accusations and broken horns. It didn’t matter if it was poetry or particle physics, all the lecturers started with a promise to get at the meaning of things. Yet thirty minutes into their explanations they were (as Byron said of Coleridge) obliged to explain their explanations. It was as if every subject was itself subject to Verlaine’s warning: Je vous dis ce n'est pas ce que l'on pense / I tell you it's not what one thinks. It was as if the will to explain anything was doomed from the start. Yet there they were, in books and on podiums, trying to explain it anyway.

☆

With Martine you knew that any attempt to explain her was doomed. Even by the way she looked at you, you knew that it would be impossible to understand what was going on in her head. She didn’t even attempt to explain. Indeed, she made it clear that the more you knew about her, the more you knew you didn’t know. It could have been the College maxim.

Sometimes Ken thought she’d spent so much time reading French philosophy, losing herself in the pages of Sartre’s alienation, that she’d become an alien herself. She looked around her as if she were scanning for radioactive traces or interstellar vibrations. Hmmmm, what are these microbial humans up to now? He couldn’t understand her unearthly detachment. Or was she just French?

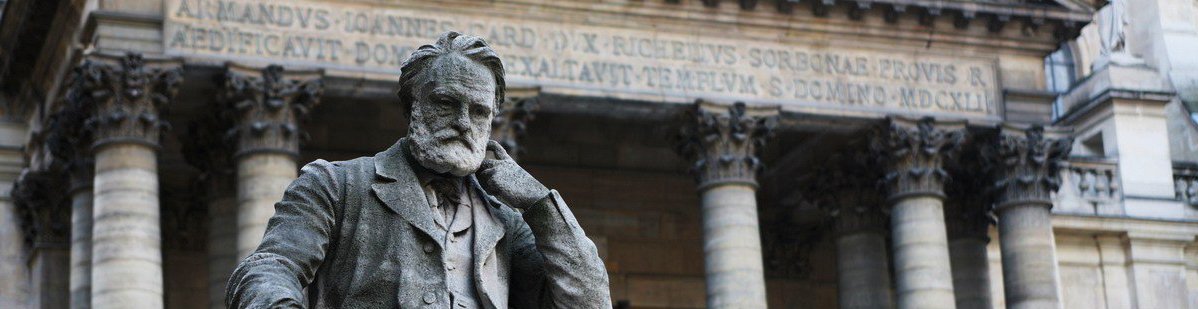

Martine once said that she was Corsican, and that her grandparents had migrated to the mainland because of some difficulty with another family. He often saw her put her hand into her jacket and look up into the sky, as if she were sending eight battalions to certain death across the Rhine. She commanded the waiters, her professors, the president of the Sorbonne, the mayor of Paris, even the President of the Republic, who was hopelessly in love with her. All of them pretended to have minds of their own, but when she told them to do something, they obeyed. Napoléon avait cinq cent soldats.

Late in the evening, the senators from the Luxembourg Palace admitted that they didn’t know what to do with her. In the nearby bars of Saint-Germain, they stared into the depths of their brandy snifters and confessed that they didn’t expect this sort of thing from a woman. Of course, the next day Martine found out about these comments, and couldn’t stop laughing.

Behind the shuttered windows of the Élysée Palace, the President refused to drink. He needed to stay sober to deal with this level of interference. The Russians were amateurs compared to her. The Chinese were flunkeys. It seemed that every time he was urged to do something by the President of the European Union, the same thing had been suggested to him a week or two earlier by Martine. He saw her the other day on Place des Ternes having an afternoon coffee with the American first ambassador.

The President refused to drink, until midnight, at which point he sighed, got up from his leather chair, and opened his teak cabinet full of vintage Armagnac.

☆

Sitting, waiting, Kenneth thought about Martine. And because he wanted her to be there and she wasn’t, he also thought about Antoine.

How he hated the man! It irritated him to see Antoine ride up to the curb in front of the Sorbonne on his mobylette. Antoine always wore tight black leather pants, so thin you could see his penis pointing more or less upward. Kenneth called it the Leaning Tower of Penis. Antoine also wore the same tattered collection of Serge Gainsbourg t-shirts every day, as if he were a poor student instead of a professeur agrégé at five-thousand euros a month. He strutted in front of his students like a metrosexual peacock. He spouted ridiculous theories about the relevance of Japanese cartoons and the music of Lady Gaga — anything to ingratiate himself to the latest fads and the slimmest legs. It would have made Victor Hugo vomit.

Kenneth also hated the way Antoine wore his beret tilted on his rich, dark hair. Could he be a bigger stereotype, a bigger show-off? The beret was cocked to one side, as if he were about to paint a lily pond in Giverny. He was a walking, scootering caricature of a French bohemian, a baby bobo, wrapped in tight leather.

And of course Antoine’s favourite restaurant was this cursed Maison de Verlaine. Its dark corners were hidden from street view and its table-cloths draped onto your knees, so that you couldn’t say where a leg stretched accidentally or where a hand glided beneath the folds. He hated the whiteness of the cloth napkins.

He imagined Antoine catching mid-air a splatter of whipped cream that flew from Martine’s fork, frustrated as she was at having to pretend to be interested in his Japanese comics. These were the same pink and blue comics that Antoine gave her as little presents. The same ones that ended up beneath her books on literature, psychology, and sociology, which were themselves beneath her nearly-finished Ph.D. thesis, titled Drama for Drama's Sake.

In her thesis she argued that Art wasn’t what oft was thought yet ne’er so well expressed, nor le mot juste, the sculpture of rhyme, art for art’s sake, or poetry that has no other aim than itself. She argued that these definitions promised freedom, yet only delivered freedom from doing all sorts of other things. Instead, Martine argued that art was drama for drama’s sake: its motives and its intentions were to play out our internal conflicts. What Hamlet said of drama could be said for Art itself: it’s a mirror up to nature.

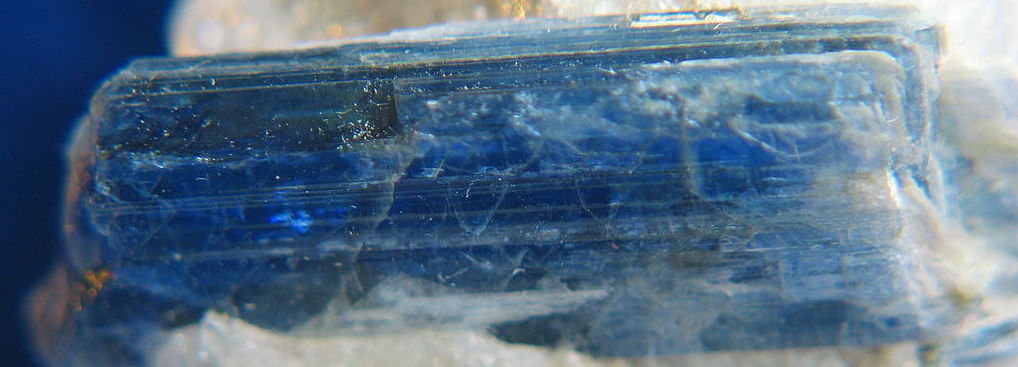

Martine hadn’t told Kenneth yet about her final chapter, Drama Queen. It brought everything into the present. In it, she argued that most of what we do is imitation, but much of what we might do is Art, from imagining your fate in a thesis that was as much conjecture as argument, to exposing the blue tints of kyanite to a robot who couldn’t say what was really on his mind.

Kenneth was sure that Martine could become a star, if only she would stop wasting time on comic books and afternoons with Antoine at La Maison de Verlaine. He admired her immensely, and yet she drove him crazy. Literally crazy, to the point where he clenched the tablecloth as if it were Antoine's throat. Beneath the cool English façade he displayed to the amusement of his French colleagues, Kenneth yelled at her imaginary image: Why’d it take a year to tell me you were once engaged to that pretentious twit?

☆

Martine said she would try to be at La Maison de Verlaine by noon. Kenneth neither believed nor disbelieved he’d see her there, let alone by noon. In trying to predict her behaviour he was a complete agnostic. It was as if every atom of her being followed Heisenberg’s principle of uncertainty.

Yet now he had this inkling inside him, this intuition, this vibration of neurons. Was it the result of waves or particles, or some hidden subatomic structure acting deep inside his brain? Whatever it was, he felt she’d be on time. He felt she was just exiting the Saint-Michel station, smiling at the prospect of surprising him by being on time.

Martine was in fact smirking as she stepped onto Boulevard Sant-Michel. She was thinking that he was thinking that she’d always be late.

He ordered a steak-frites and a glass of wine, and sat back to work out this business about the kyanite ring. Perhaps he could even work it into his lecture that afternoon.

Until the kyanite ring, his reasoning had gone like this: If you believe in existentialist probability, then you believe in the immorality of chance. For instance, the hundredth time you get on a plane you have the same chance of crashing as the first time. It doesn't matter if you’re good or evil, if you’ve flown a million times or never before: your chances of crashing are just the same as those of everyone else. It’s not fair, and certainly not moral, but that’s just the way it is. That’s the way the dice tumbles over itself. Roll the bones.

If, however, you believe in essentialist probability — in a metaphysical system that controls the physical universe, giving justice and meaning to our actions — you believe in the morality of chance. Your chances of being in a plane crash increase with every successful flight. It’s only fair that you crash as often as everyone else. Even if one kept individual justice out of the equation, there would still be some bigger essentialist Plan that brought the plane down or kept it in the air. Probability became less a detached constant based on pure chance in a random universe than an involved variable based on a larger system of metaphysical justice. In such a case, probability lost what Kenneth called its mathematical, existential, immoral purity.

Then along comes this damned ring. Martine’s telepathic experience (if indeed it existed) meant that we’re influenced as much by erratic vibrations and by incalculable correspondences as by either random chance or higher Scheme of Things. The ring, which allowed some sort of arcane communication, created a gap between the existential self and the physical world because the self could no longer count on a world of pure chance. It also created a gap between the essential self and the metaphysical world because —

“Ken, you’ve started without me! C’est pas très poli, ça.”

Kenneth looked up. A bel visage floated toward him, smirking through the ether of an uncertain arrival. X x X = Martine. He managed to fumble out, “I - I wasn’t sure you’d make it.”

As she sat down she objected, “But I told you — ah, qu'importe! I can’t stay long anyway. Antoine is taking me somewhere this afternoon. It's a bit mysterious, but I think he’ll take me to meet Nakata. You know, the manga artist. Antoine hopes they can do a French Schoolgirl Thriller. Like the Michael Jackson video with Vincent Price.”

The waiter was hovering patiently next to the table, with only the patience that a Parisian waiter will show for a beautiful woman. “Et pour Madame?”

“Juste un cafe. Merci.”

“Oui Madame.”

Martine sat back in the red cushions and took a deep breath, just deep enough to tighten the sheer cotton of her dress. Kenneth wished he’d never heard of Vincent Price, Michael Jackson, manga, or the ever-talented master of all things shiny and new, Antoine Lacrotte.

Antoine’s surname was Lagrotte, but Kenneth preferred Lacrotte. It gave him pleasure to imagine Antoine on his beaten-up mobylette picking up dog excrement, like Chirac’s infamous motocrotte gang that once kept the side-streets of Paris clean. Antoine the Pooper-Scooper. Antoine de Saint-Expooperie. Kenneth even wrote a little story about Prince Antoine driving all over the universe looking for poop to scoop. He sent the story to his sister in the faraway city of Edmonton, where even in the month of April they scattered salt on the frozen sidewalks. She wrote back a sarcastic one-word response: “Charmant!”

As Martine breathed out again, she asked, “So, what will you be lecturing the old ladies on this afternoon?”

The way she emphasized lecturing made it sound like boring them to death. OK, so it wasn’t a racy crowd. Claudia Cardinale wasn’t sitting in the front row, waiting for him to answer her burning question about the meaning of love.

Kenneth often thought about the actress when he saw Martine. She was that beautiful — and that sure of herself. Claudia once said in an interview, “If you want to practise this craft, you have to have inner strength. Otherwise, you’ll lose your idea of who you are. Every film I make entails becoming a different woman. And in front of a camera, no less! But when I’m finished, I’m me again.”

Kenneth responded, “I plan to lecture the old ladies on Pascal and probability theory."

Martine seemed to want to humour him, probably because she had something to tell him about Antoine. Perhaps they were going to another comic conference in Barcelona. Tapas, sangria, the whole auberge espagnole. She leaned into him and asked him to refresh her memory. “Ça doit être fascinant. What exactly are the probabilities?”

Kenneth looked at the necklace between Martine’s breasts.

The kyanite drew him into her world. Everything he said seemed to confess an argument like the one she made when she put her fingers up to her lips and told him about the ring.

He couldn’t admit it, but he didn't know what the probabilities were. He didn’t know why he felt the way he did. He wasn’t sure of anything. All he knew was that he wanted to stay with her, drinking bottle after bottle of wine. And stop her from going to see Antoine. He didn’t give a damn about his lecture or about Pascal’s God.

She thought to herself, And he thinks he knows everything.

☆

Next: Le Bijou 3: The Third Act