The Double Refuge ⏯ Systems

Unlimited Agnosticism

Either/Or, or Neither - Walking the Line - Neither / Both - My Friend Harb

⏯

Either/Or, or Neither

Hard-core theists and atheists argue that you have to choose either God or science, either belief or disbelief. Hard-core agnostics sometimes play this game, deciding to appreciate neither.

Hard-core agnostics are similar to those who stand proudly, refusing to be influenced by all the currents of history within them. They distance themselves from science because it hasn’t explained everything, and they distance themselves from religion because it’s not subject to proof and because one religion can’t be squared with the next. Other agnostics give the benefit of the doubt — rather than the restriction of the doubt — to all serious philosophies and epistemologies.

Like agnostics, theists and atheists can also choose to apply inclusive doubt or restrictive doubt to belief systems that differ from their own. For instance, some Christians read Aristotle and Origen, Rumi and Zhuangzi, and feel enriched by the different currents of thought. Other Christians divide Christianity from science, and then divide their brand of Christianity from all the others. They then build up the significance of their particular brand so that it fills the gaps left by the rejection of the other brands. Likewise, one Sikh entertains all the currents of thought from Benares and Bodhgaya to Mecca and London. Another divests himself of Veda and Koran, Bible and On Liberty, cutting off his nose to spite his face.

Restrictive agnostics are more heir to divestment than to wealth. Their’s may be a proud and independent divestment, but it’s one that isn’t so much the sum of its parts, as it is a part that calls itself the sum. They have disavowed their roots, and yet these roots are, however well hidden, still parts, if only they looked deeply enough into history, philology, and human nature. Such restrictive agnostics find themselves walled in between the order of laboratory and university on one hand and the beauty of temple and mosque on the other.

Inclusive agnostics on the other hand remain open to both religion and science. They remain open to all the traditions which precede, surround, inform, and affect them as human beings. As a result, walls fall away. Fences become markers rather than borders. The world looks new at each turn, opening out into field, funnelling into corridor, or blasting down highway.

The doors of the buildings that once seemed restrictive are open. The buildings themselves are crystal clear, translucent in the sunlight. Or they glow like gold in the blackness of the night:

⏯

Walking the Line

Restrictive or limited agnostics are like American voters who, tired of the Democratic circus, fling themselves, as from a cliff, into the void of the independent, forgetting that they don’t live in Canada or Germany, and that there’s no third choice. But for inclusive or unlimited agnostics there is a third choice, albeit one that can splinter into four, five, six, and as many choices as they might make as they walk the broken and at times invisible line between theism and atheism. Or as they jump down from that line that has become a fence, and wander among the choices on either side, always knowing that they always have a choice. They can stay as long as they like on one side, and on any pathway on any side, or they can hop back on the fence, look around, and continue walking the line.

Agnostics who throw themselves into the independent camp are limited agnostics because they limit their options. They must build their world up, like the purist Sikh who rejects the rich traditions of Hinduism and Islam. My analogy works here even when it doesn’t seem to: even the purist Sikh has already borrowed from both sides – karma samsara from Hinduism, and the community united around one God from Islam. The purist Sikh might argue that Umma has nothing to do with Khalsa and that Sikhs have nothing in common with Buddhists who threw out the caste system two and a half thousand years ago. But to pretend to have invented religious truth is to weaken the very legs on which you stand.

Wise Sikhs understand this, and don’t make a fetish of their particular version of faith. Instead, they avail themselves, as their gurus did, of poets from either religion. They find parts of themselves in the Sufi poets and the Hindu storytellers, and other parts of themselves in Guru Nanak, John Stuart Mill, and the world traditions of their diaspora. These Sikhs, like many Ismailis and Reformed Jews, make of their religion an unlimited truth. Taking away the capital from Truth operates in much the same way as taking away the capital from Catholic.

⏯

Neither / Both

Hard-core theists and atheists would have us believe it’s either/or, it’s belief or disbelief. Yet for agnostics it’s neither/both, and it’s better to lean toward both.

To choose neither creates an unnecessary distance from Copernicus, Hutton, Darwin, Rawlinson, Watson, and Crick. It’s also to avoid Attar and Rumi, Muhammad and Hadith, Purana and Gita, Shankara and Vyasa. One makes a very thin wall of oneself in doing this. One might be proud to stand on this wall, disdaining the peaks of science and religion, yet a wall between mighty opposites isn’t as powerful as the opposites themselves.

Better to follow the wise Sikh, who sees the formulations of science and religion as speculations, as trails to follow, into the jungle vines or the desert sands, to see what lies on the horizon. And more than this: to see that the horizon itself moves. As Tennyson puts it, “all experience is an arch wherethrough / Gleams that untravelled world whose margin fades / For ever and forever when I move.”

Religions, sciences, and doubts aren’t resting places or final destinations. Who’s seen such a destination? Rather, they’re invitations to a journey.

⏯

My Friend Harb

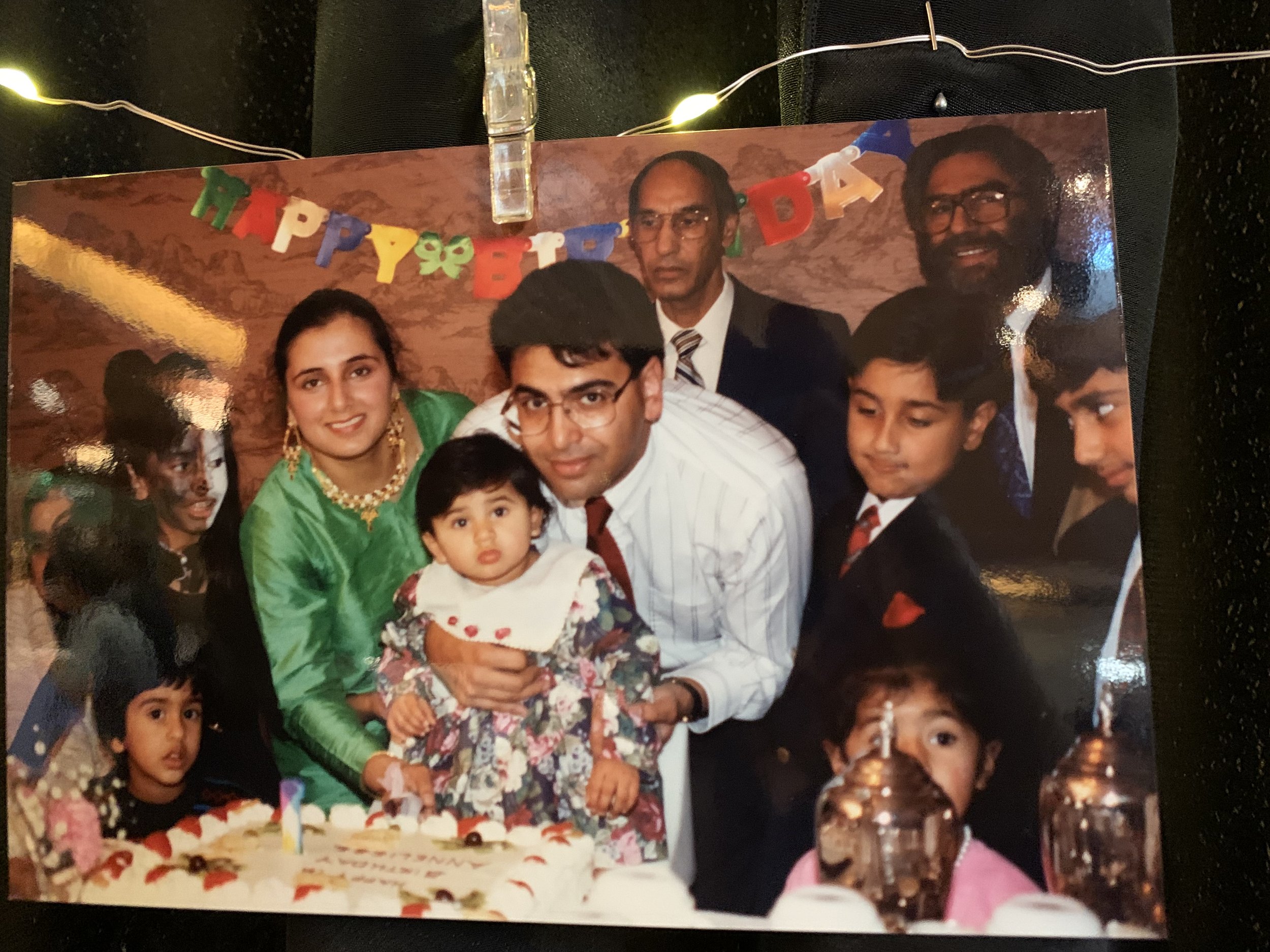

I’d like to acknowledge here that much of what I say about the inclusive Sikh comes from my friendship with Harb Sanghara, my office mate at UBC in the late 1980s. I spent countless enjoyable hours discussing with Harb the merits of Blake and Byron, the fine line between morality and liberty, and the cultural nuances of religion and disbelief.

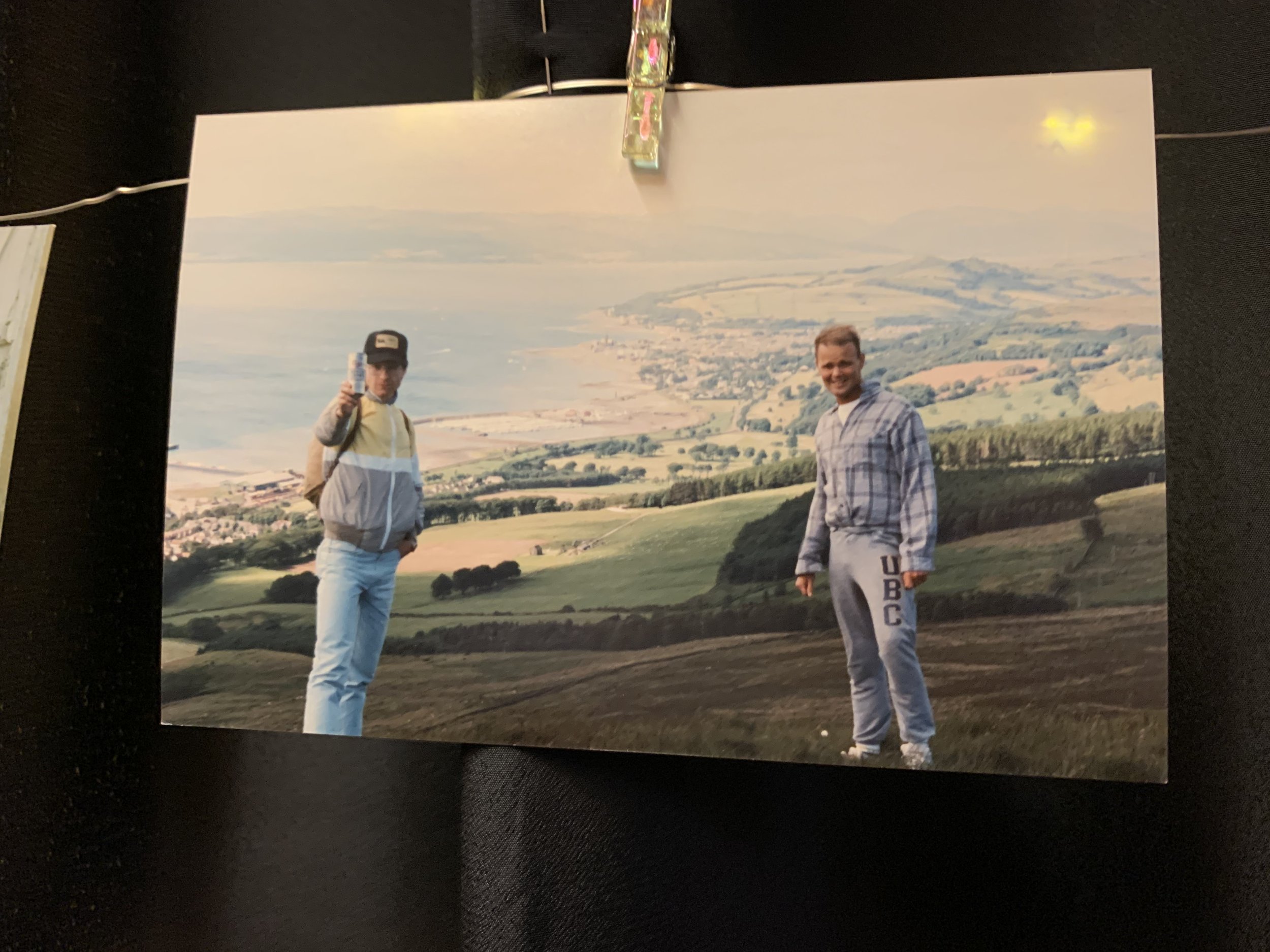

Harb died recently, but I’ll always remember the twinkle in his eye and the wonderful trip we took in 1989 from Scotland to Turkey — including three fabulous, serious, riotous weeks with his relatives in Bradford, Lichfield, and Birmingham.

I took the following shots with my iPhone at his August 2023 memorial at The University of Victoria, where he taught for several decades. His wife Livleen (in the last photo) had put up a wall of photos. The first was taken by Harb in Ayrshire, Scotland, where we were visiting Ian’s family. Cheers, my friend!